THE FAMILY PAPERS

History is tricky.

History is tricky.

We have only the records of the past to construct our knowledge of what happened before our immediate witness. Even when the history explored is our very own – experienced and remembered – the truth is slippery.

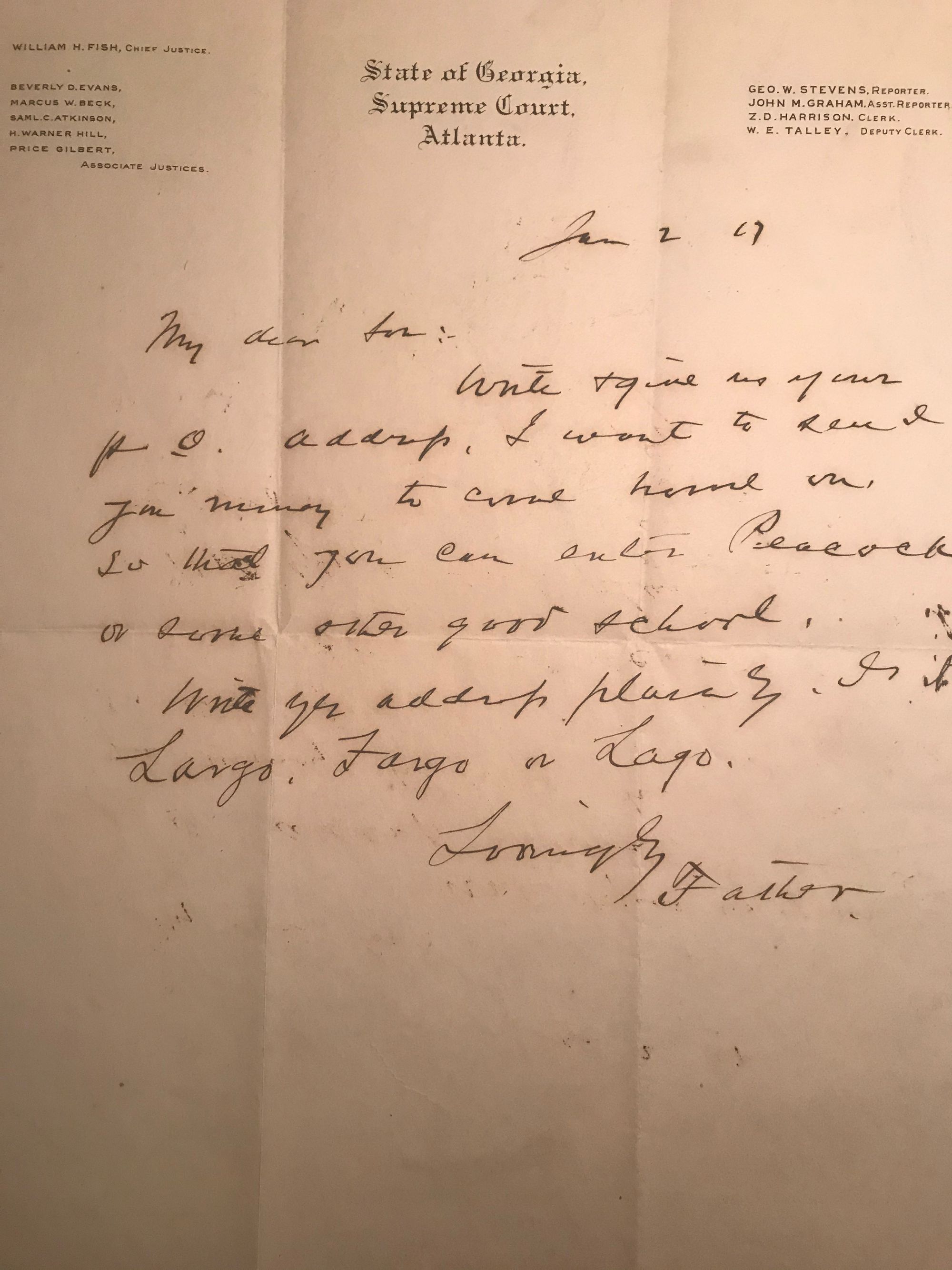

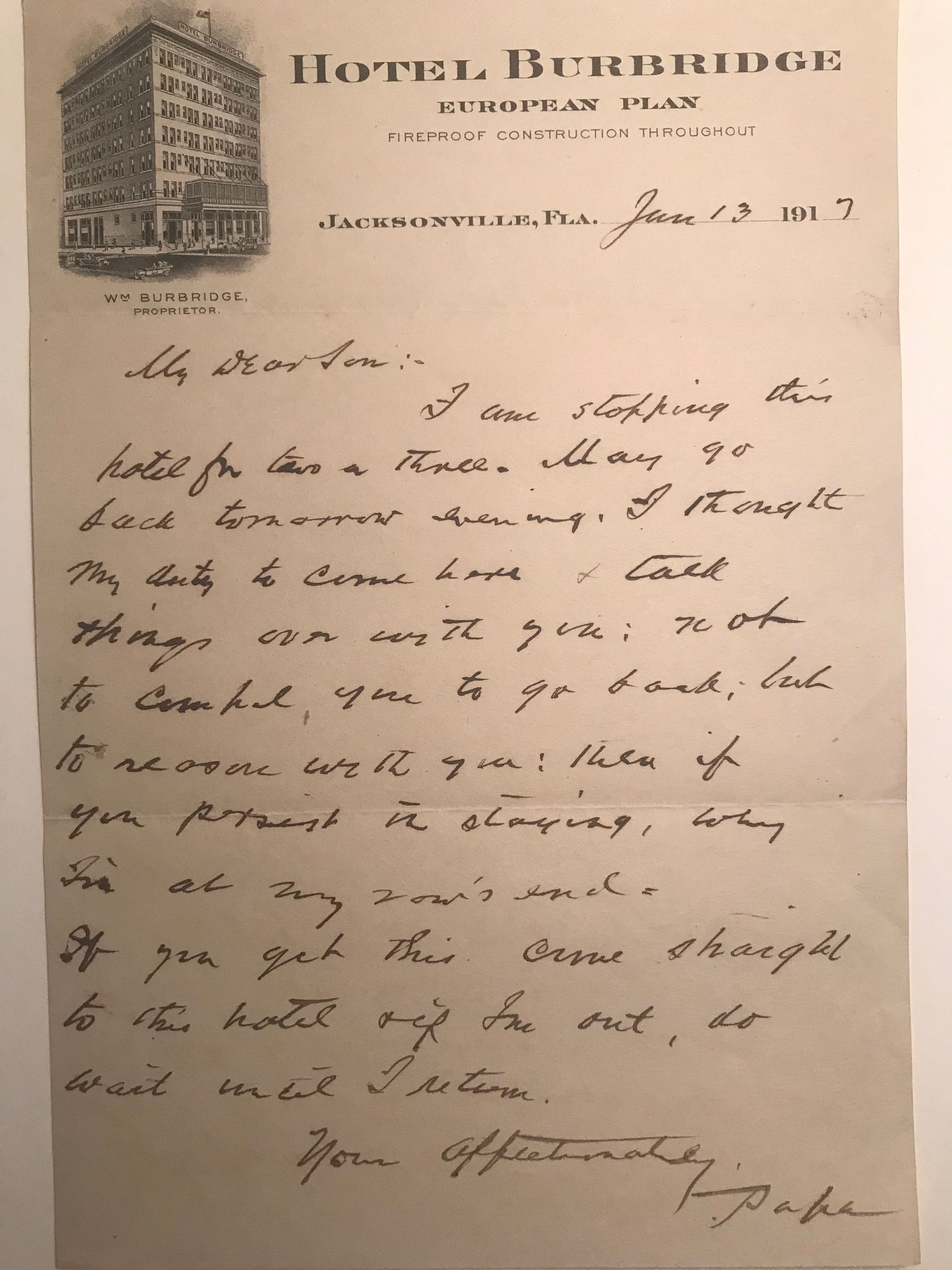

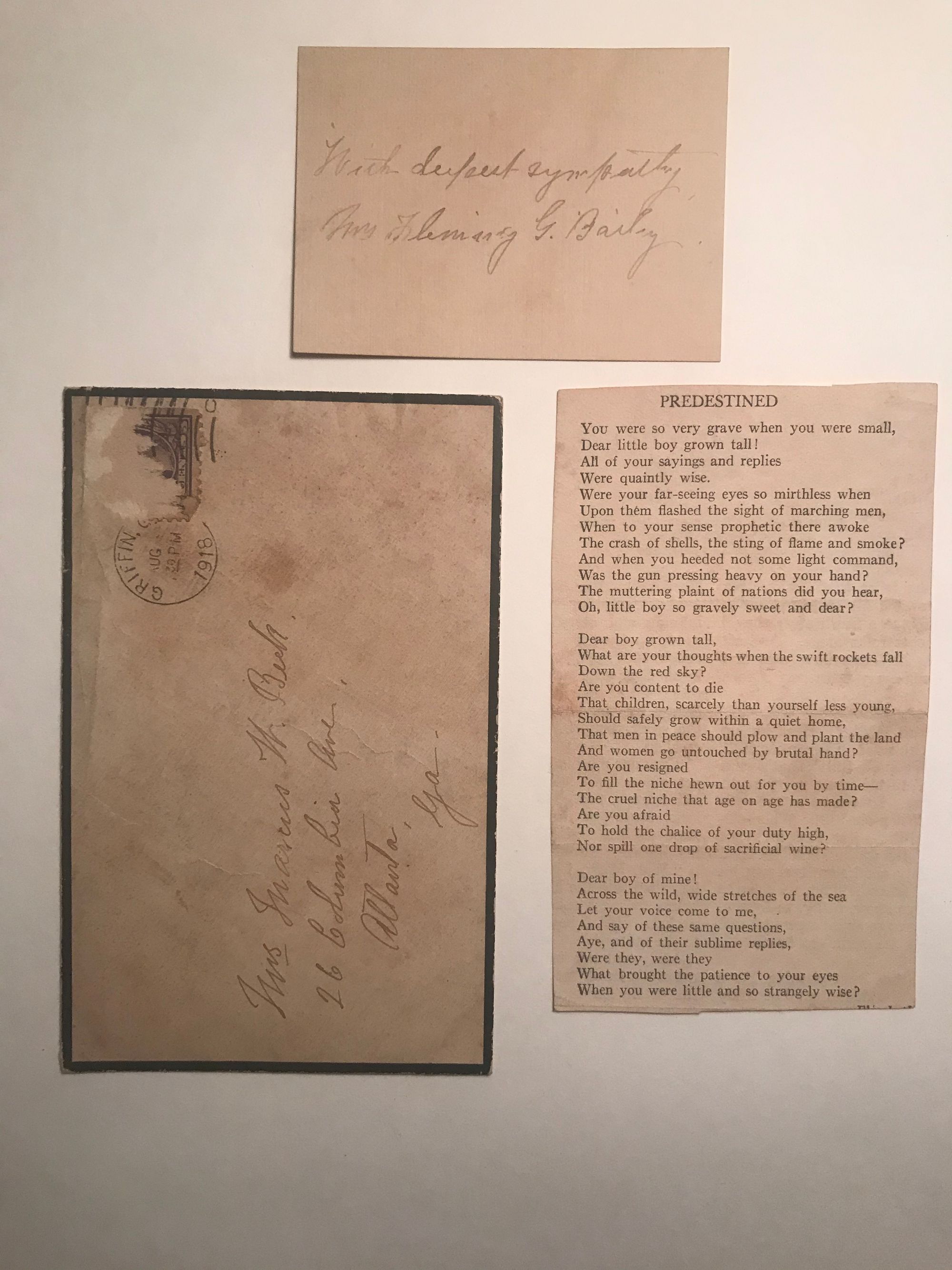

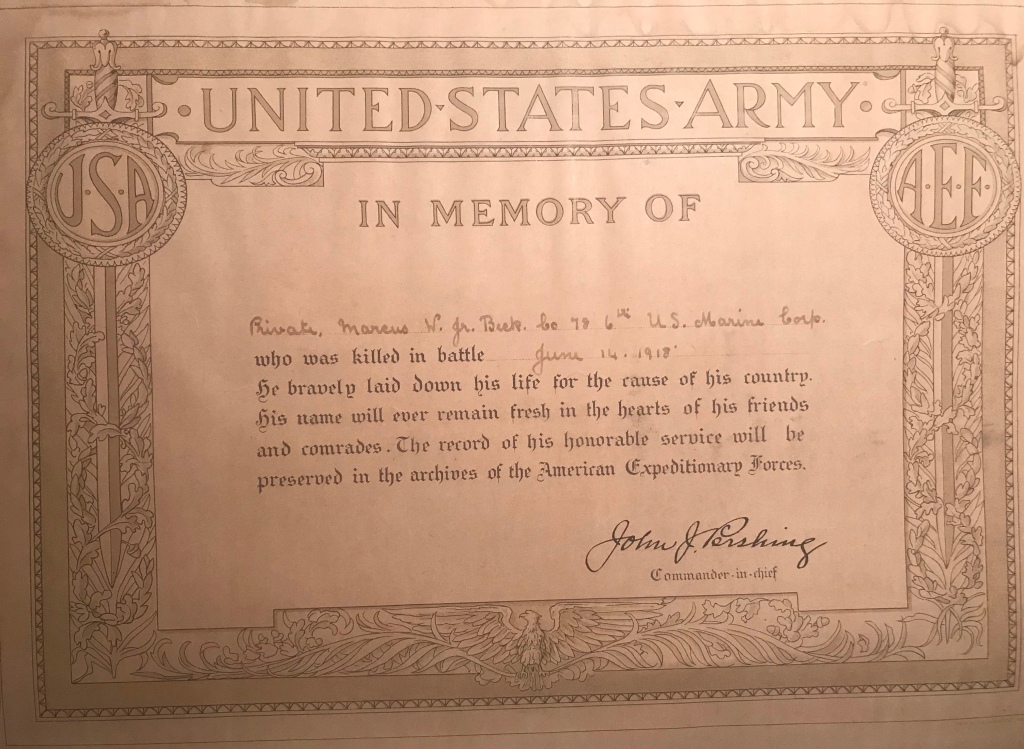

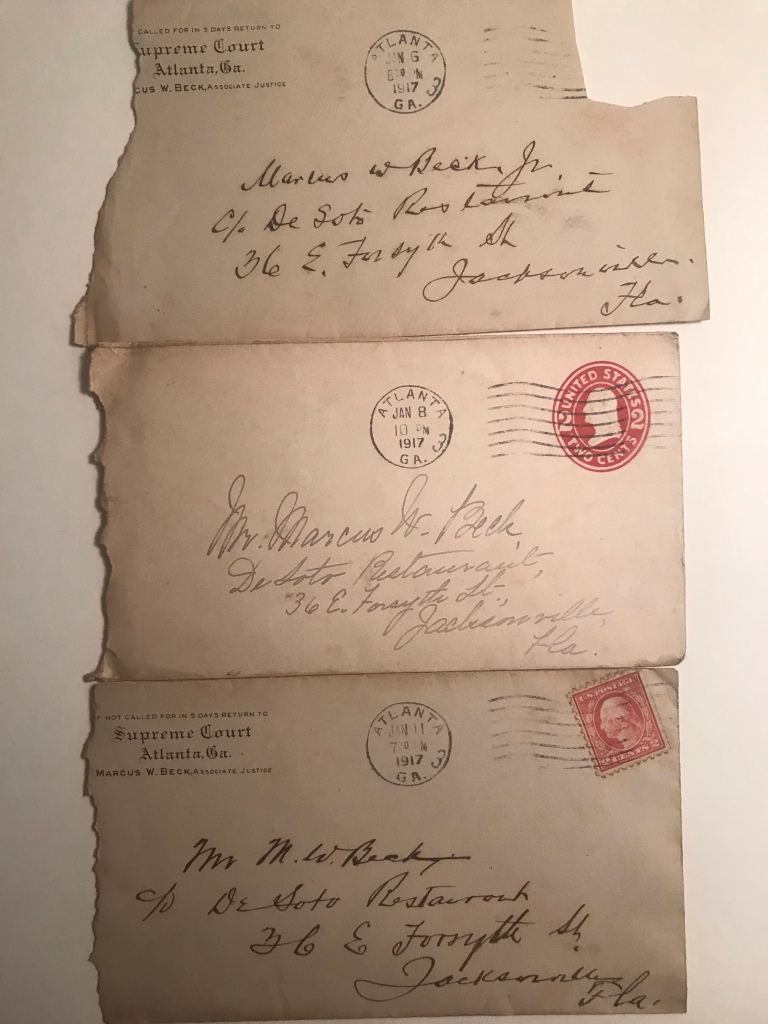

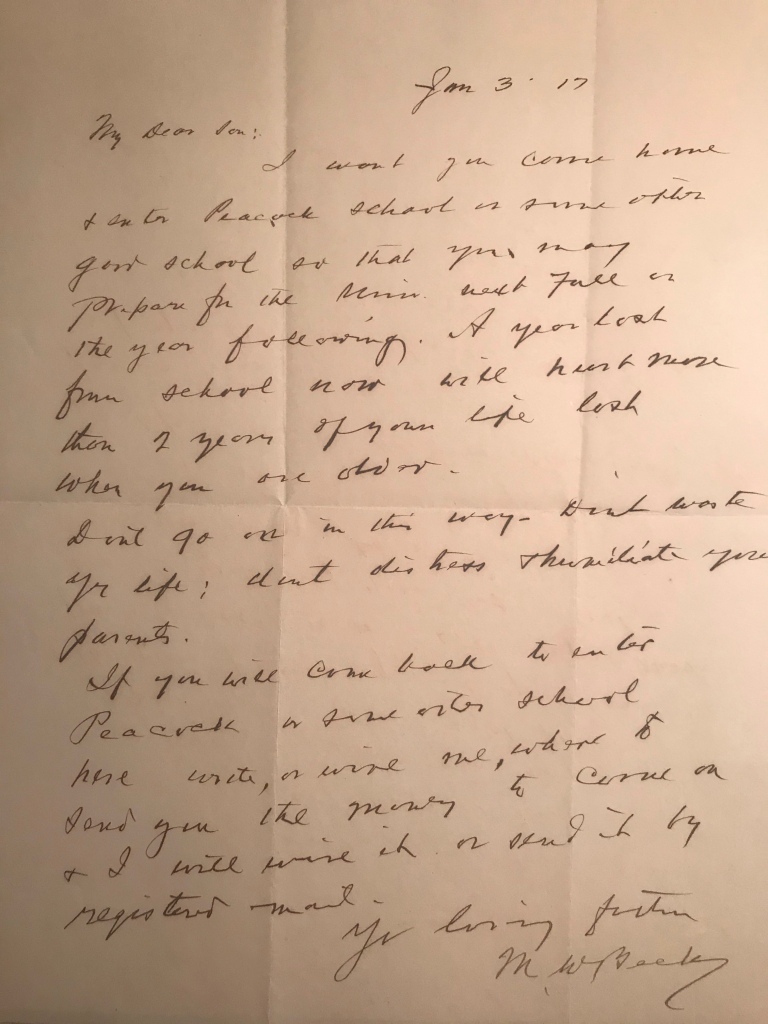

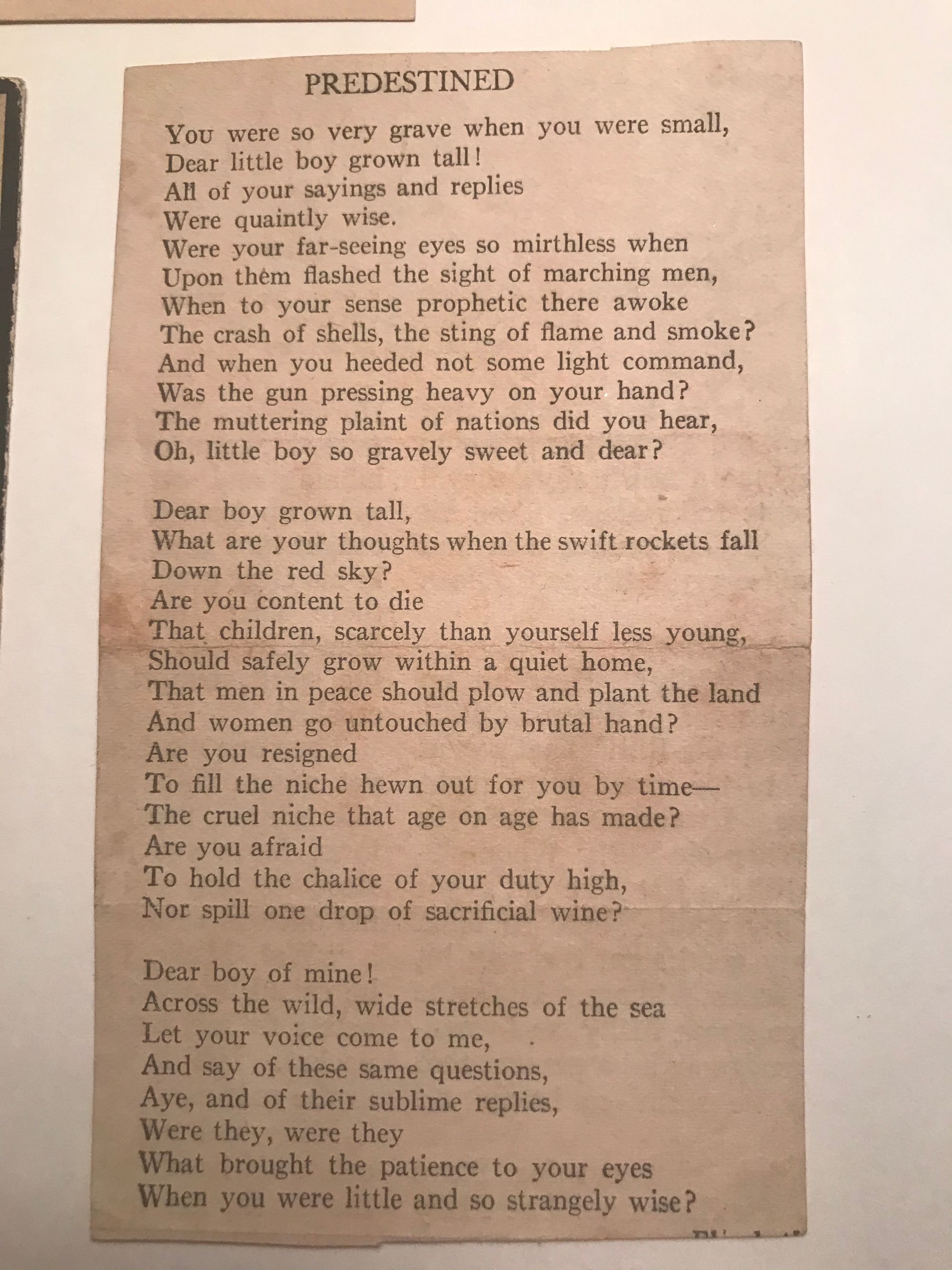

This is an incipient autoethnographic process, meaning that I’ve only recently begun to review, catalog, and transcribe the ‘papers’ stored at my parents’ house, which detail through saved letters and documents – a receipt for a train ticket, a certificate given for having died in the war – my great-great uncle’s running away from home at age 16 in 1917 and his subsequent experiences in the Marine Corps training prior to being deployed to fight in WW1. He died in mid-1918, just 18 months after he had written home from his run-away to Florida that he wanted to be an architect.

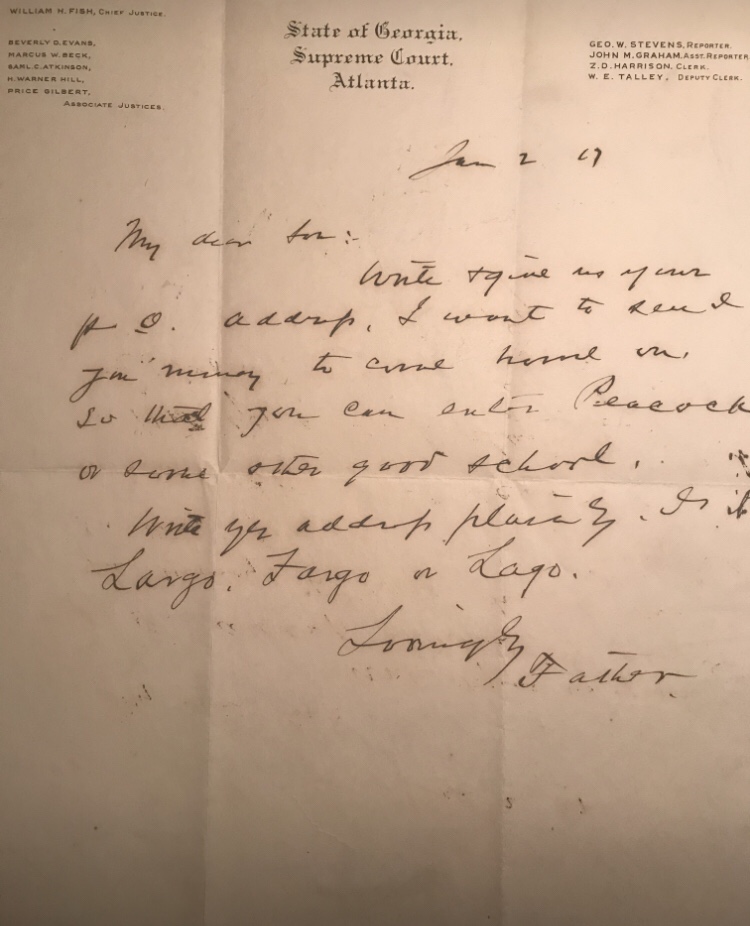

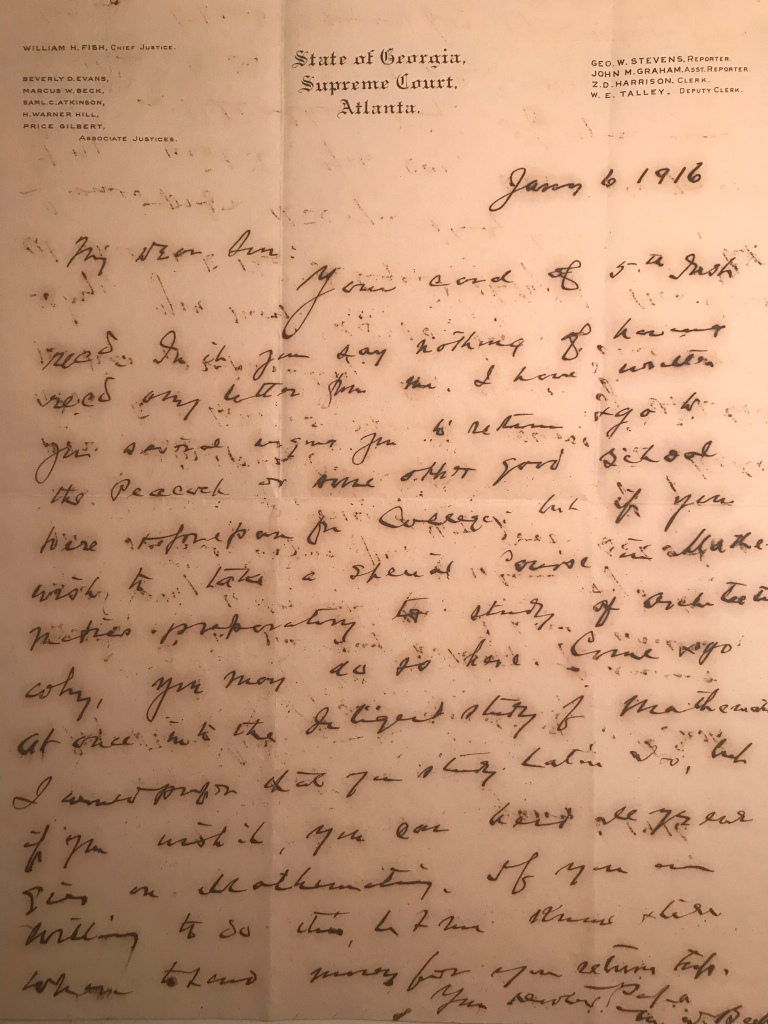

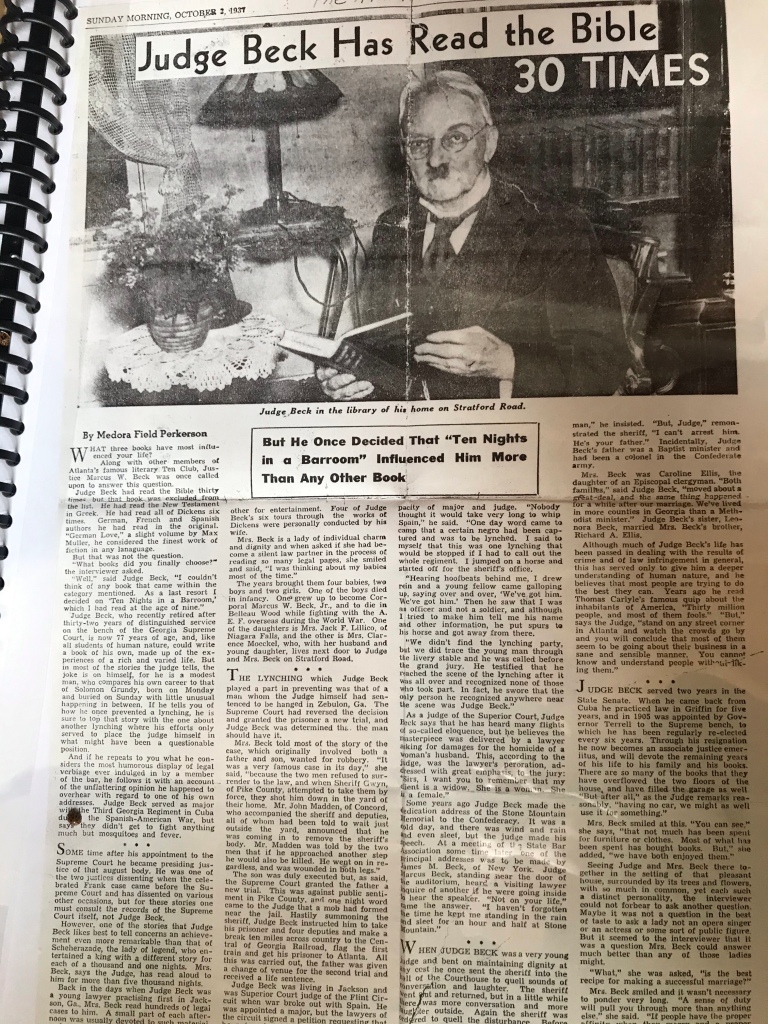

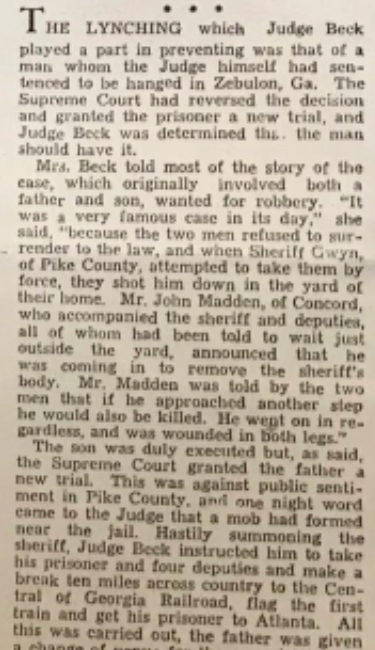

His father – my great-great grandfather was a presiding Georgia State Supreme Court judge during the same era that gave rise the 1906 race riots in Atlanta and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

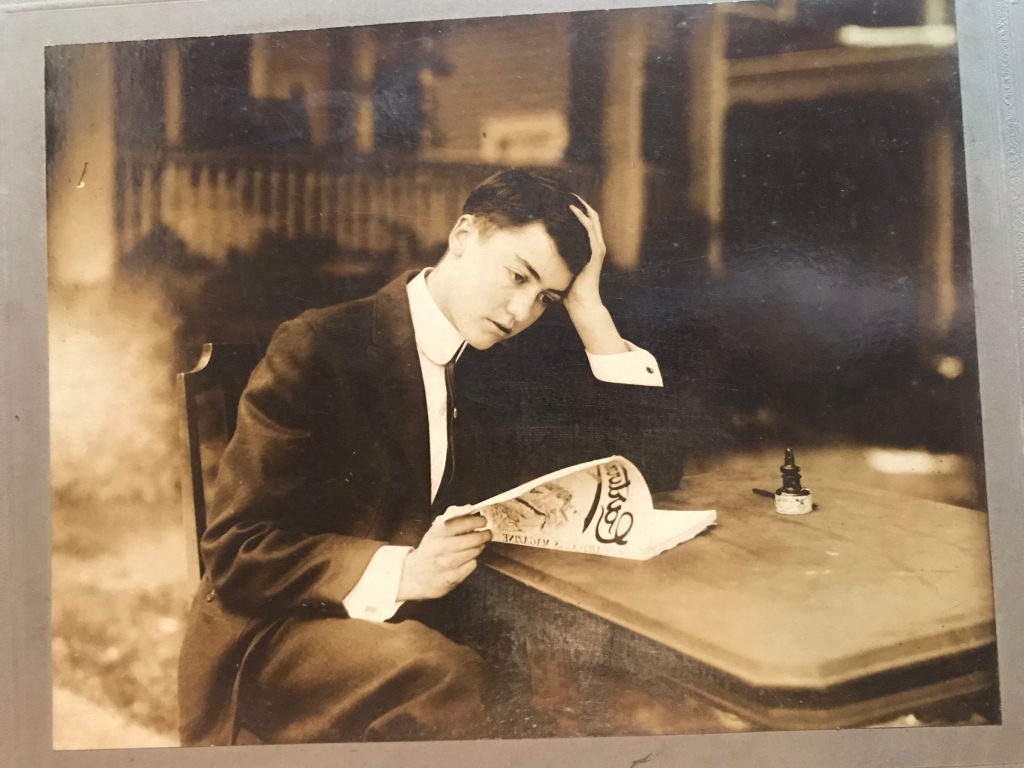

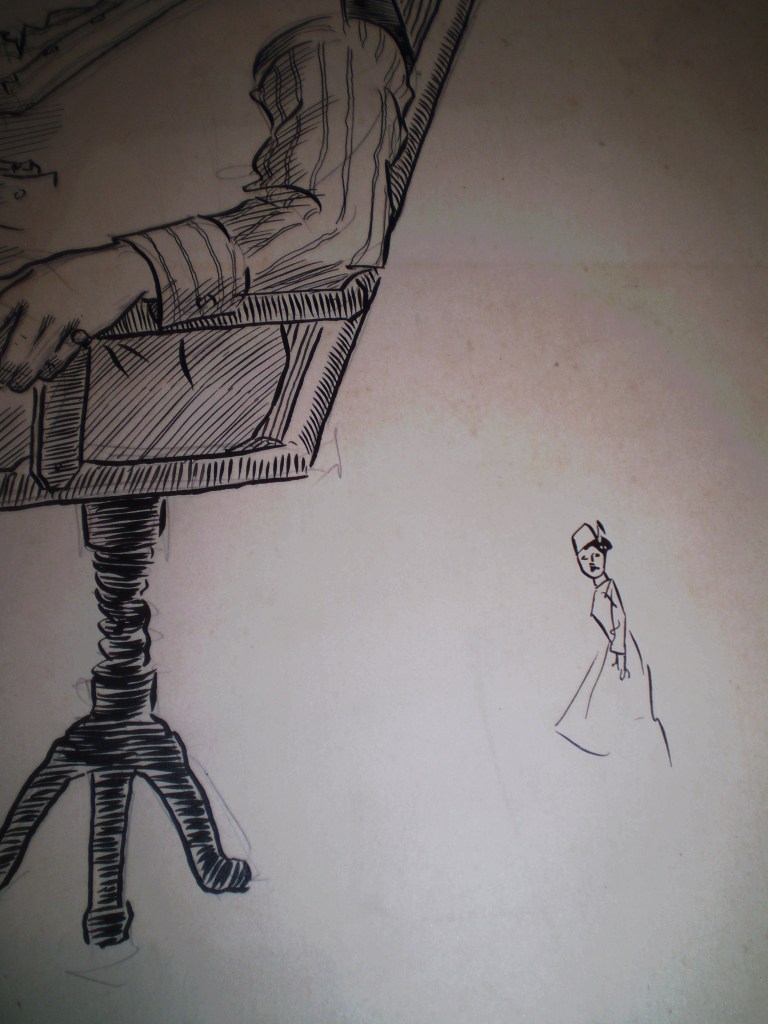

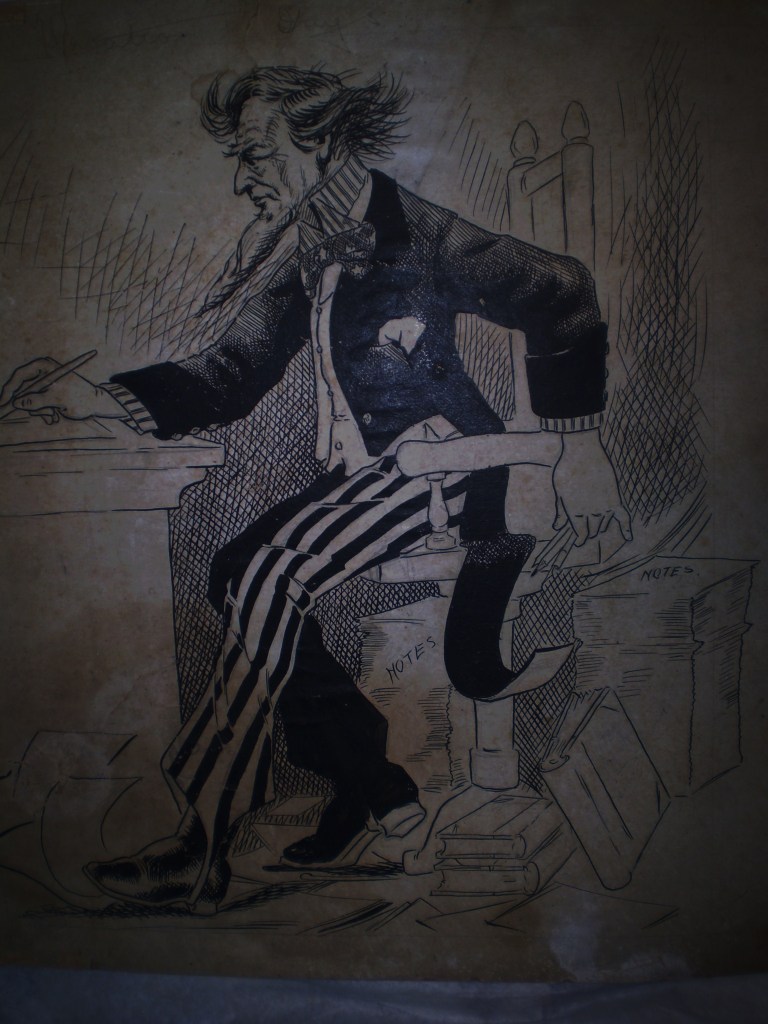

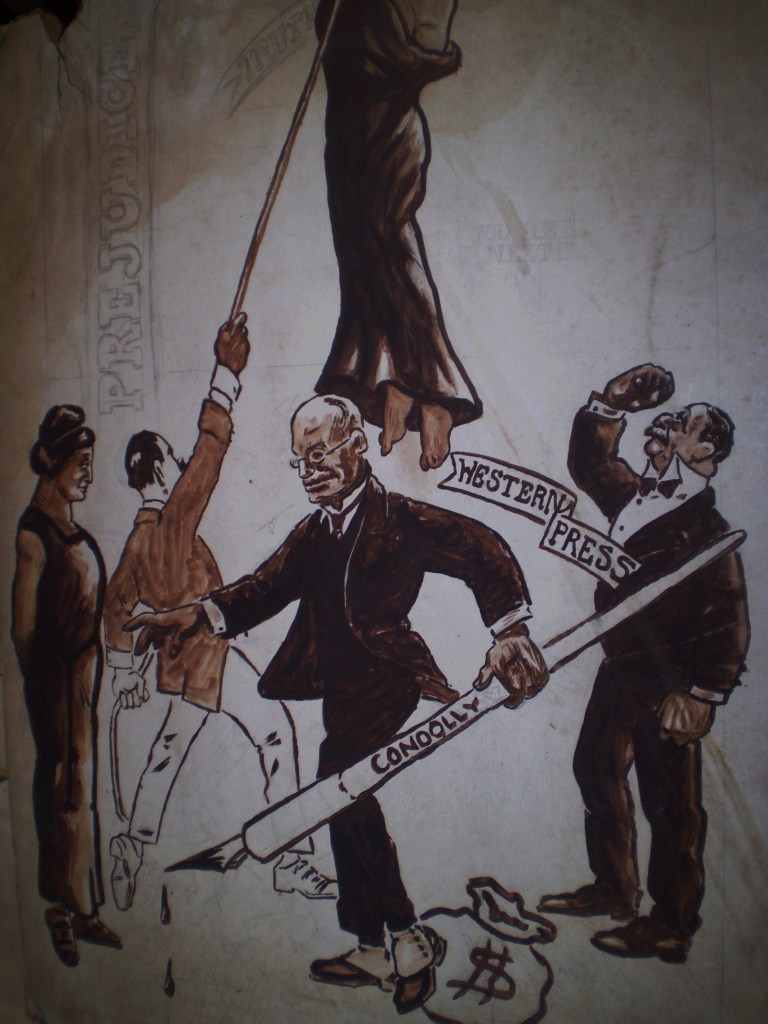

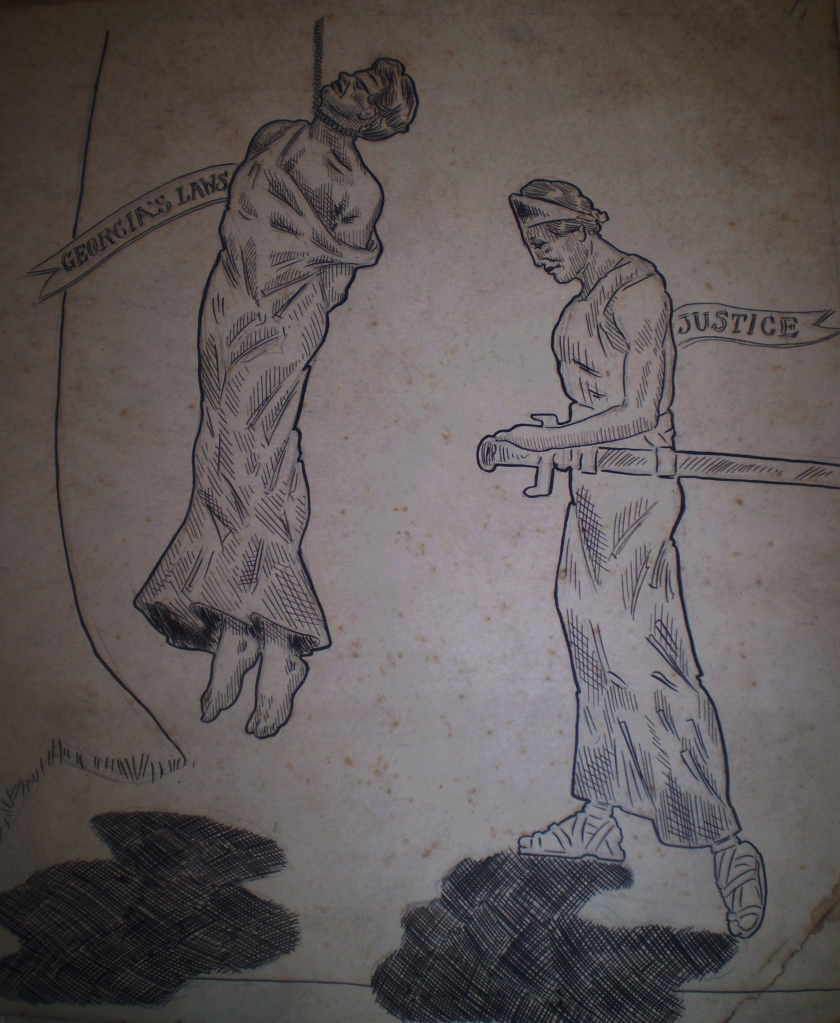

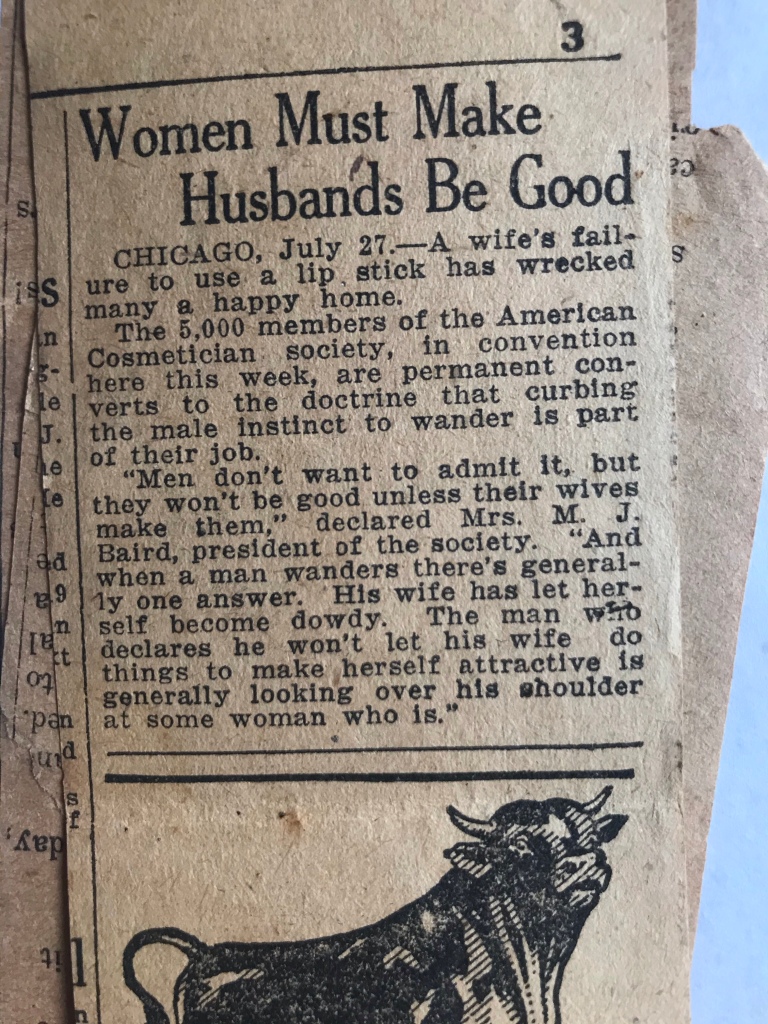

Marcus W. Beck, Jr. – son of the judge and my favorite dead uncle – was an artist and, as his pen+ink drawings make clear, a staunch opponent to prejudice and lynchings.

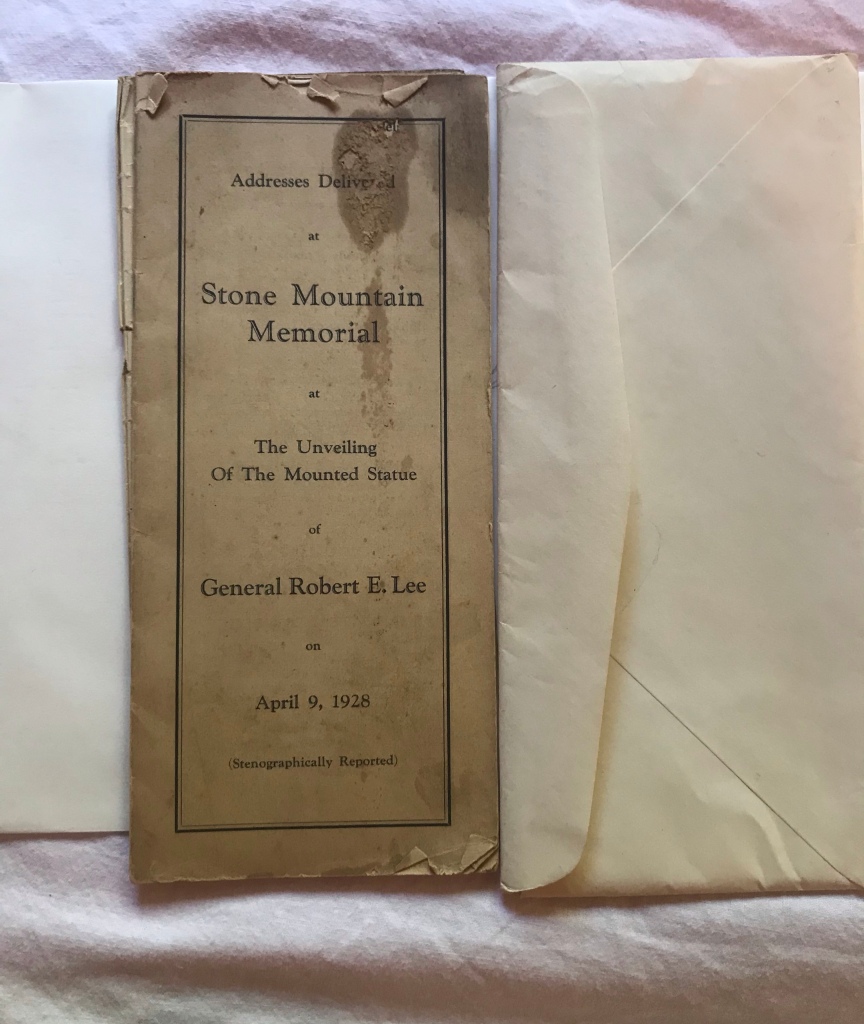

Ten years after his son died at the Battle of Belleau Wood in France, Judge Beck accepted the carving of Robert E. Lee at Stone Mountain, Georgia on behalf of the South.

As I consider this cache of family history from my father’s bloodline, I am reflecting on my experience of learning about this particular branch of my ancestry – my thoughts and feelings about this history I am discovering, my judgements and laments.

I am deeply considering why I may feel so conflicted, sick, and sad to think about the story of my great-great uncle Marcus who was an artist that wanted to be an architect and his father the Judge-with-a-dead-son going on and on in his long-winded acceptance of the Robert E. Lee monument while the crowd stood in an uncharacteristically cold April rain waiting for him to finish his speech.

I don’t know what it is about humans that make us so fascinated with what came before our brief little time, our nanosecond lives on earth.

Who am I?

Who are my people?

What happened to create the world that I understand to be real?

What are the stories that define who I am?

I grew up in the American South, and am – if I count back the sons and daughters correctly – a 6th or 7th generation Georgian on my father’s side.

It is worth noting that – in my opinion – nobody other than the descendants of indigenous people can justly claim multigenerational ancestry tied to any place in the lands we call North America, as their ancestral lineages stretch back thousands of years.

The rest of us Americans are the descendants of immigrants, refugees, or colonial conquerors.

Although my mother is from Florida, her grandparents immigrated to the United States from Lebanon in, I believe, the 1890s. They had intended to go to Albany, New York, but due to what is explained as ‘getting on the wrong train,’ they ended up in Albany, Georgia at the edge of the 20th century, just three decades after the end of the American Civil War.

Although the Nicholas (ex Khoury and al-Shahaidi) family eventually moved to Miami, they lived in Georgia at the same time my father’s great-grandfather was gaining judicial stature.

My maternal grandfather – brown eyes, brown skin, tightly curled black hair, a mother who spoke little English – was born in 1907 in Albany, Georgia, the year after the riots in Atlanta.

I know nothing of his childhood and very little about my mother’s Lebanese ancestors in general, who they were, where they were from, what their experiences as immigrants held.

As an adult, the man who would become my mother’s father married late to a young switchboard operator named Faith, who had come out of an abusive family line in Alabama. They had 3 daughters and lived on SW 23rd Terrace in Miami, a small house with Spanish tiles on the roof.

When their youngest daughter – my mother – was 10, my Lebanese grandfather dropped dead of a heart attack on a business trip to Jacksonville, the city I would be born in 16 years later.

He was an low-level executive in the Florida Milk Co. The few pictures of him are photos of him at work, black and white company photos.

In photos, he is the only brown man in the room, but he is smiling, and looks happy, a light in his eyes. He seems American in his suit and tie.

His family spoke Arabic until they learned English. My mother called her paternal grandmother sit’ti and in the 1980’s, I ate kibbeh, lebneh, and khubz arabi when we went to Miami. My mother made lentils and rice as frequently as she did spaghetti, prepared spinach pies with shreds of American orange cheese instead of lemon juice and vinegar.

I am the only one on my mother’s side of the family who has studied Arabic, who made an effort to learn the language of where some of my people are from, a language that was forgotten in the ever-present glare of necessity to speak English, to be American.

I imagine that people in Albany, Georgia at the turn of the 20th century might have…what? Disliked the Lebanese immigrants? Discriminated against them?

I don’t know. I can imagine all sorts of things, but I have no facts and – like I said – facts are dubious when it comes to history.

Judge Beck was appointed to the Georgia State Supreme Court by Governor Joseph M. Terrell in 1905, a year before the Atlanta race riots of 1906.

The term ‘race riots’ may not be an accurate descriptor for the events that took place in Atlanta the September that my great-grandmother was 11 and her brother – Marcus Beck, Jr. – was 8 or 9.

What happened in Atlanta in 1906 was a massacre, ‘a mass beating, a mass lynching. The term ‘race riot does not name the details and descriptors of what happened in Atlanta.

‘Race riot’ does not explain that a violent mob of 15,000 – 20,000 white men raged through the city destroying Black-owned businesses and gathering places, killing dozens of Black people in the streets. The official death toll was 25. Nobody knows how many Black people really died. Some estimates place the death count at over 100.

Only two white people died, and one was a white woman who had a heart attack after seeing the violence in the streets outside her home.

‘Race riot’ doesn’t name white supremacy, or white violence.

In my mind’s admittedly imperfect conceptualizations, a ‘race riot’ means that a large group of people from a marginalized and racially-oppressed demographic group take to the streets in an angry and unruly manner in outraged and grieving response to race-based injustices. Property may be damaged, such as the burning of police vehicles as a response to police brutality, and opportunistic looting may occur.

A ‘race riot’ does not mean a small army of demographically distinct people sweeping through a city, entering neighborhoods and killing people from another demographic group.

‘Race riot’ does not mean 15,000 white people – (Men and boys, mostly, I’m almost sure, as it was likely not proper for white women and girls to be out in the street committing acts of violence, though if one has ever seen the ugly hate on the faces of white school girls protesting school integration in the mid-20th century, 50 years after the Atlanta race riot, it is easy to imagine white women and girls cheering on the brutality committed by their male counterparts.) – publicly killing dozens of Black people and going out of their way to destroy Black-owned businesses, burning Black homes.

It was not until 2006 that the Atlanta race riots were even officially acknowledged by the state of Georgia.

I can recognize in myself a subtle sense of embarrassment, a sheepishness, in admitting that I had no idea that there was a ‘race riot’ in Atlanta when my great-grandmother was about to turn 12, when her Papa – as they called him – had just become a Supreme Court Judge the year before.

The Atlanta race riots of 1906 were not part of the Georgia History curriculum taught at Mary Lee Clark Middle, Camden County, c. 1988.

Although I have a minor in Black Studies with a BA in Sociology from Portland State University, I don’t remember any African-American History courses that mentioned the Atlanta race riots. This event probably was taught, perhaps in a lecture crammed full of the brutal beatings and racism-fueled fires of the early 20th century in the American South – but, I took those classes 25 years ago and – to be honest – a lot of history just blurs in my mind, the details and names and dates slurring into a cluttered timeline of mass atrocities that leaves my heart heavy with the enormity of how many ugly things happen in the world.

I wonder what it was like for them, the children of the house. Rachel and Marcus, their older sister Margaret. Their father was an important man, had become an important man. Their Papa was a judge. They were home with their mother, going to school. I don’t know what their lives were like, the day-to-day of home and childhood, their little world.

One Saturday afternoon, the newspapers reported that two White women had been raped by Black men and the city exploded into violence.

I wonder if my great-great grandfather went out into the mobs. He was, after all, an ‘important man.’ He may have only watched the violence.

Regardless of whether or not he was in the streets as a ‘rioter’ – it is very, very likely that he contributed to the violence – condoned it, perhaps even sanctioned it, agreed to allow it, conferred with the Sheriff and deputies who – it is said – openly participated in the public beatings and burnings of business.

As I write this, I notice a sick-ish feeling in the center of me and I don’t know – specifically – why I feel this.

Is it the knowledge that accusing a Black man of raping a white woman, or – in the case of Emmett Till, whistling at or even talking to a white woman – was (and in some places, in some minds, still is) essentially a warrant for violence against the accused Black man, as well as violence against people of African descent in general?

Is it the knowledge that my great-great grandfather was involved in the establishment of structural and systemic racism in the state I grew up in, those bloody ties between injustice and the justice system?

Just as the facts of history blur in my mind, my heart’s response (and my nervous system’s response, my mind’s response) to the rampant ugliness of American history, world history, the reality of slavery, old mothers mourning stolen sons in Sierra Leone) is less a specific facet of feeling and meaning, and more an overwhelming though quiet wash of feelings and images that sums itself in feeling sick, feeling sad, graven at the center of me.

My ability to articulate any sort of coherent incisive reflection or analysis is blunted and stammering, regressive almost, stammering like a child about how it’s just so grossly wrong, all of it.

“All of what, Faith?”

“All of it! People and society and stores and wars and this disgusting commodification of every fucking thing, rape culture, slave economies, police brutality. All of it.”

I feel like spitting. My hands are tingling with wanting to clench. I can feel something big and righteous in my chest, an aggression. An anger. I am an outraged child, tormented by the dissonance of knowing that people I love and who I want to see as good people do things that I know are deeply ugly, wrong, deplorable.

It’s interesting to think about the perspectives of the white men who took the streets in a killing mob one Saturday night. They were probably feeling righteous about themselves and what they intended to do. In the context of who they were and the times they lived in, they probably thought their actions were serving some twisted justice.

It strikes me, however, that perhaps they were also excited, that maybe they wanted to kill and destroy, that they seized the righteousness they found in the perception of themselves as the white male savior and protector of white women against a perceived threat, and allowed that male human bloodlust to be released en masse.

One thing I do remember from my African American History class is my professor asking us if we thought that any Black man in his right mind would dare to sexually assault a white woman with so many examples having been shown to him of what happens to Black men if they mess with white women.

White men had raped women and girls of African descent for generations and generations, had brutalized women and girls of African descent.

God, I feel sick.

7/06/2013

Everyday, this time of year especially, I think about my favorite dead uncle.

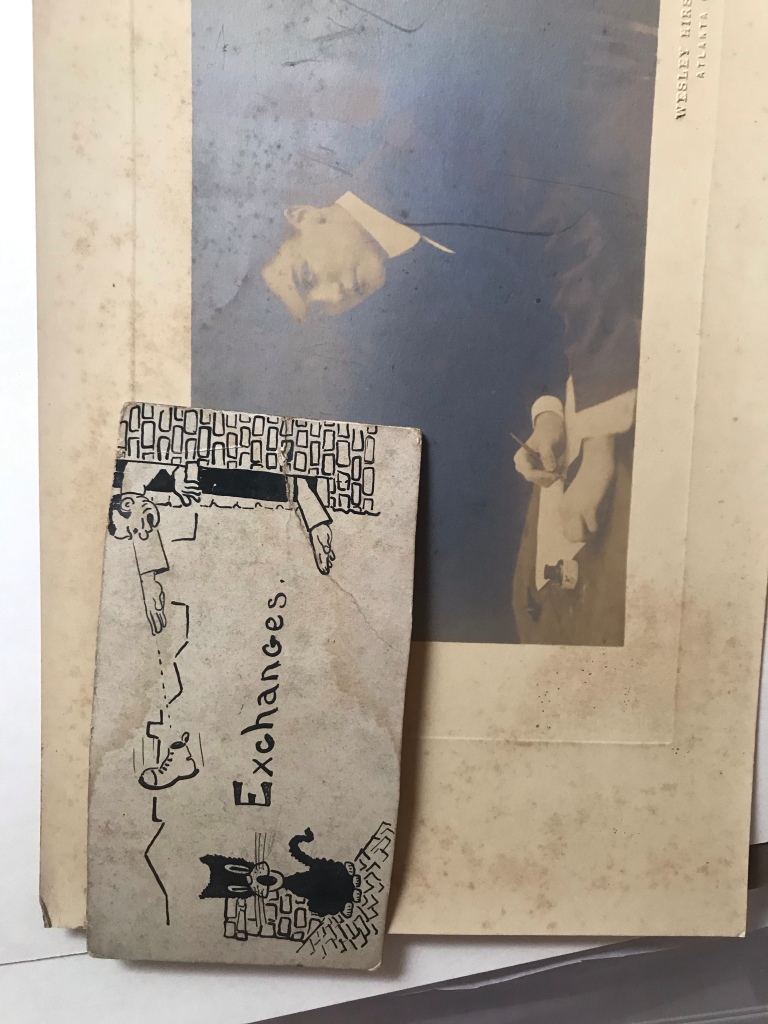

It has been about 3 years since I opened up the box of papers and set his ghost free.

How do I know there was a ghost?

I could feel it.

I don’t know why I decided to ask my father about Uncle Marcus’ letters, where they were. It’s possible that I simply remembered they existed, and wondered what had happened to them.

I was surprised to find out that the box of letters and photos was here, in the mountains.

Then again, where else would it be?

I think I wanted to see his drawings, because I was drawing a lot then – a picture every day for a year, already well into the 3rd quarter of that project and learning how to forget to try, to forget my own ideas, to let the pictures be what they wanted to be. I had started to see and to notice the shapes in everything, and remembered sitting on the wooden front steps of the house I grew up in, the Dome House – which is what my parents took to calling the stilted plexiglass and lumber icosidodecahedron and long kitchen hall with bedrooms and decks and stairways down to the grey sandy yard shaded by oaks that dropped dead leaves all year long, littered the ground with their beetle-brown shells, the Dome House on the river bend, if you break west from Borrell Creek and travel the map of the lands edge, past the point where the cedars grew and the sand was clean, smooth, almost a beach, that place once it ceased to be the place they called home – listening to my father tell me that clumps of bubbles fuse in 60 degree angles, making hexagons…endlessly and without will.

In the period of time that my adult-world marriage had thoroughly crumbled, and I had been drawing everyday, I had started to remember many of the things that I had not remembered for a very long time, and – to be honest – it was a bit much, the remembering…all the remembering.

I opened the box very innocently, just wanting to look at old things and think for a few minutes about the smell of my great-grandmother’s house and about the closet that the papers were in, the closet in the room on the shady side of the house, with hydrangea an impossible blue beneath the second story window of the room with the cabbage rose wall paper.

The closet seemed to gasp out all its dusty, old smells in surprise when the light – a bare bulb on a brittle string – was turned on with a decisively incandescent click to display in swinging shadows shelves of boxes and old rows of shoes, a war helmet on the wall with the words “War Is Hell” written across the top of the old canvas.

We knew that there were letters in the boxes, though we never saw them. The boxes were never opened. We knew the letters had something to do with Uncle Marcus, who died before ever becoming an uncle.

We know this because his sister, my great-grandmother, told us. She was the one who saved them, all that proof of the brother that she had lost.great-grandmother saved them, all that proof of the beloved brother that she had lost.

They say that he was “special, an artist.”

I was in my mid-30s when I first saw Marcus’ drawings, and understood that he was deeply critical of politics and laws…and lynchings.

As a teenager, he drew the picture above, which depicts a sword-wielding figure with a sash reading ‘JUSTICE’ hanging a classical white woman-ish figure with a sash reading ‘GEORGIA STATE LAWS.’

He was the son of a Georgia judge in the early 20th century.

When I was young, and wanting to draw pictures, people would remember him. I don’t think I ever identified with him though, except to wish that I might be special, too and to long to have enough bravery to run away to the circus, or somewhere.

My family – like most families, I guess – is full of histories that nobody ever talks about.

We did not speak of the way my father’s mother briefly married her professor, or how it was that the professor came to leave just after my father was born, the marriage annulled. For years, I did not know my paternal grandfather’s last name. I still don’t know his first name, and have never had any contact with any of the people I am related to through his bloodline.

We did not speak of how my great-grandfather died or the fact that my beloved great-grandmother was an alcoholic.

Why have I never wanted to write a book about my great grandmother?

She was the one who taught me to play cards, after all. She was the one who taught me to tell stories.

Why has her ghost never clamored at me the way her brother’s has, nagging “Tell my story, tell my story…”

Perhaps it is her, not him, that is nagging?

Maybe it is both, doing as children do, which is to try to get what they want, to get what they need, to have their voices heard.

Why else would she have saved his papers and drawings?

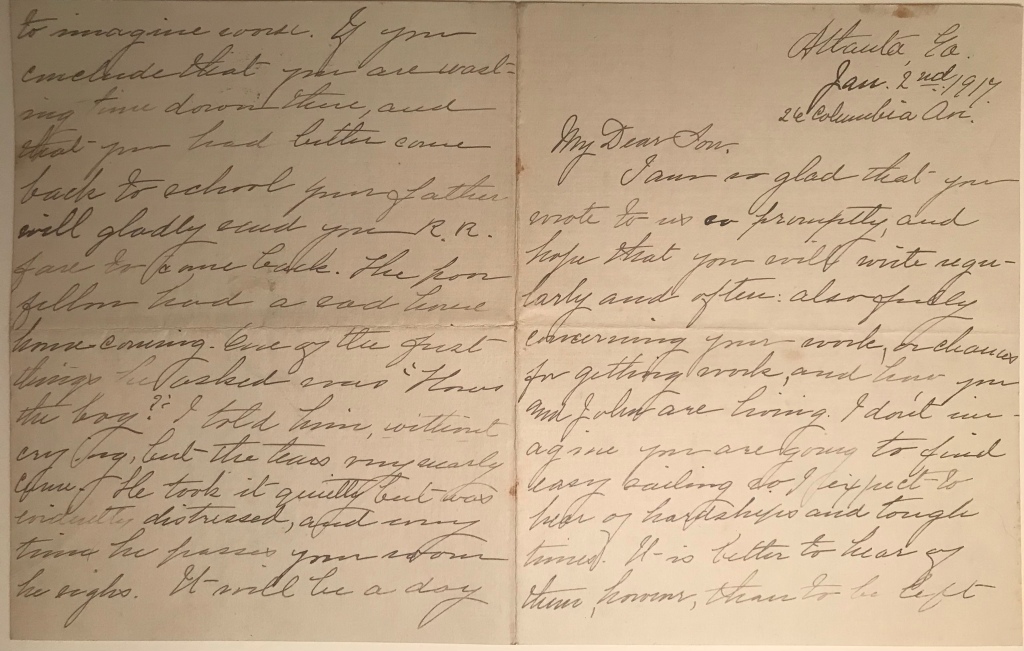

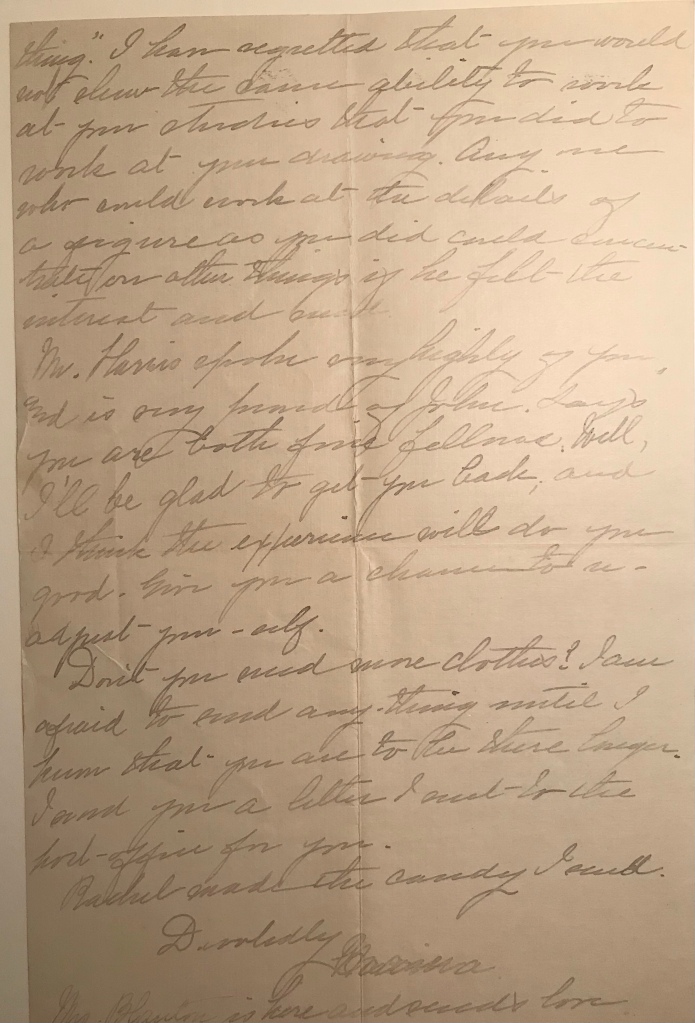

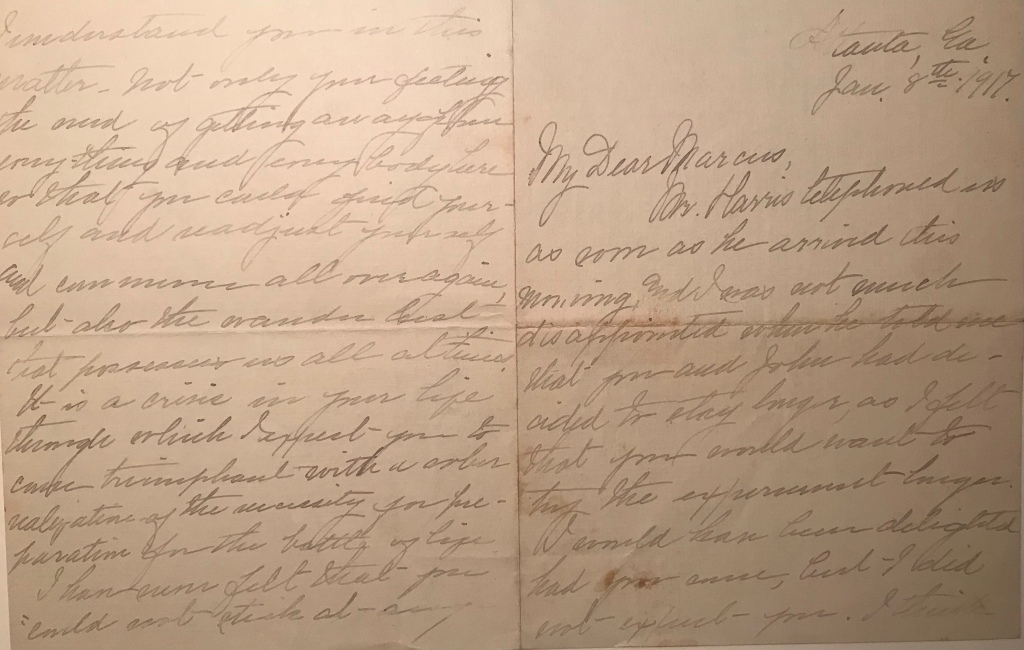

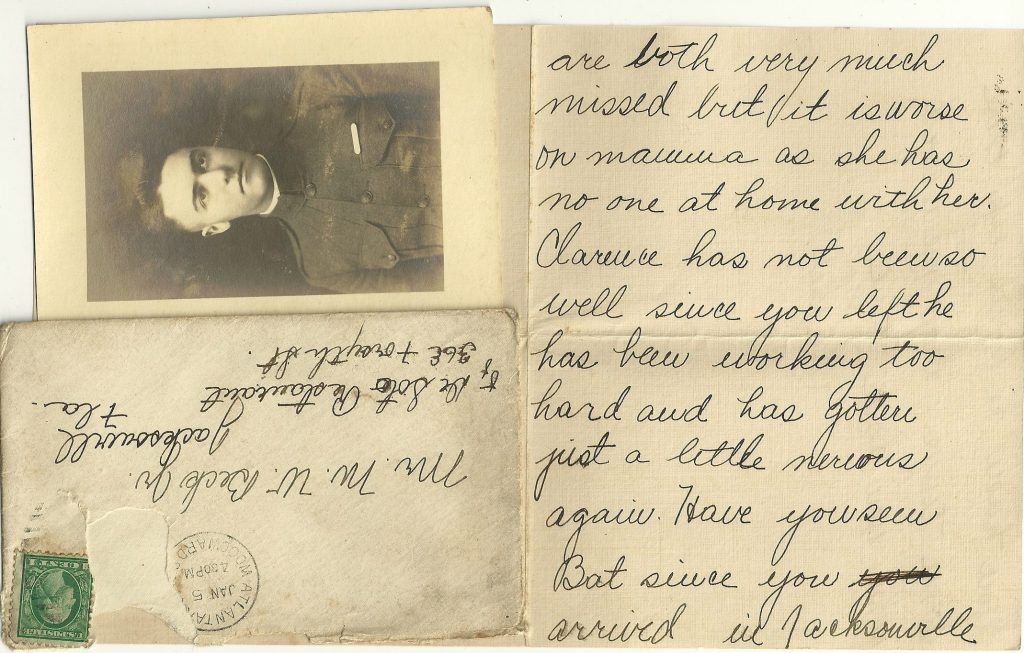

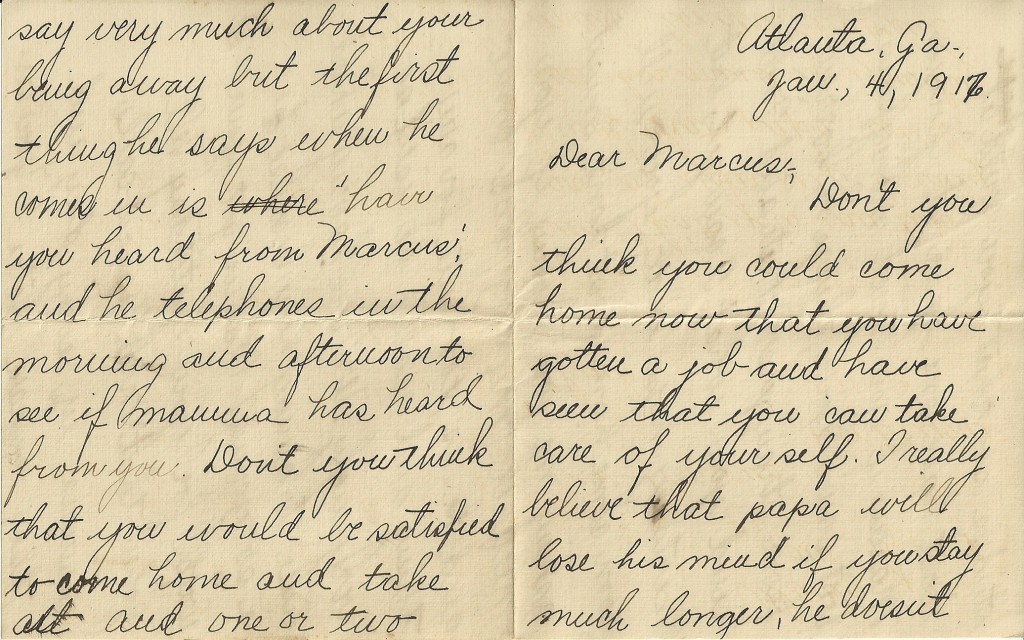

A Letter From Rachel Beck Moeckel to her Brother Marcus, Jr. (1917)

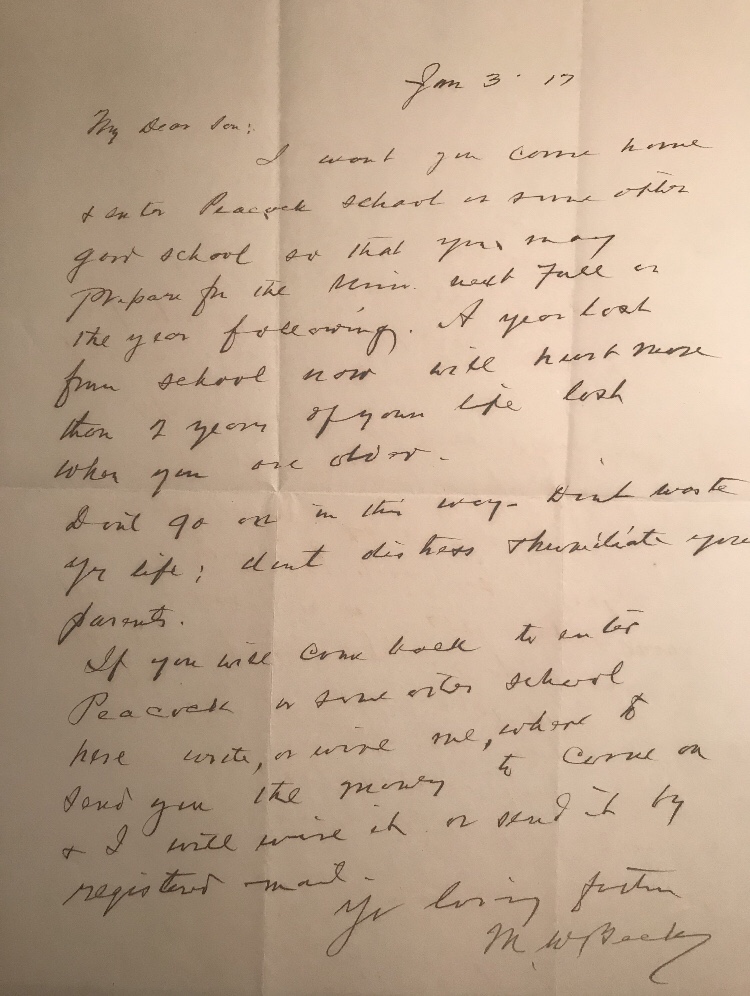

Jan 3, 1917

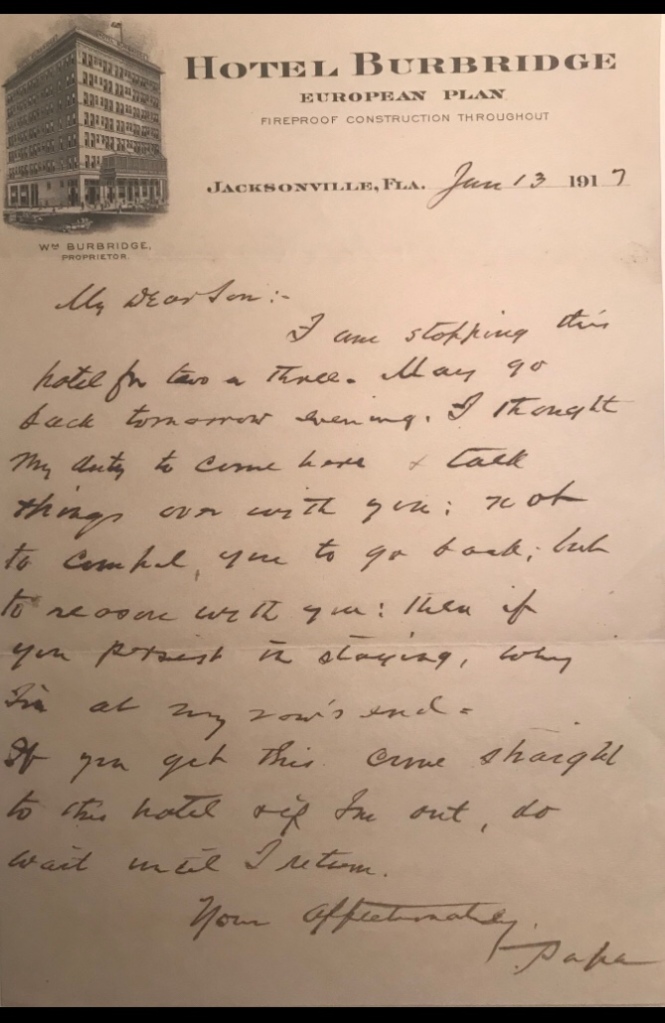

My Dear Son:

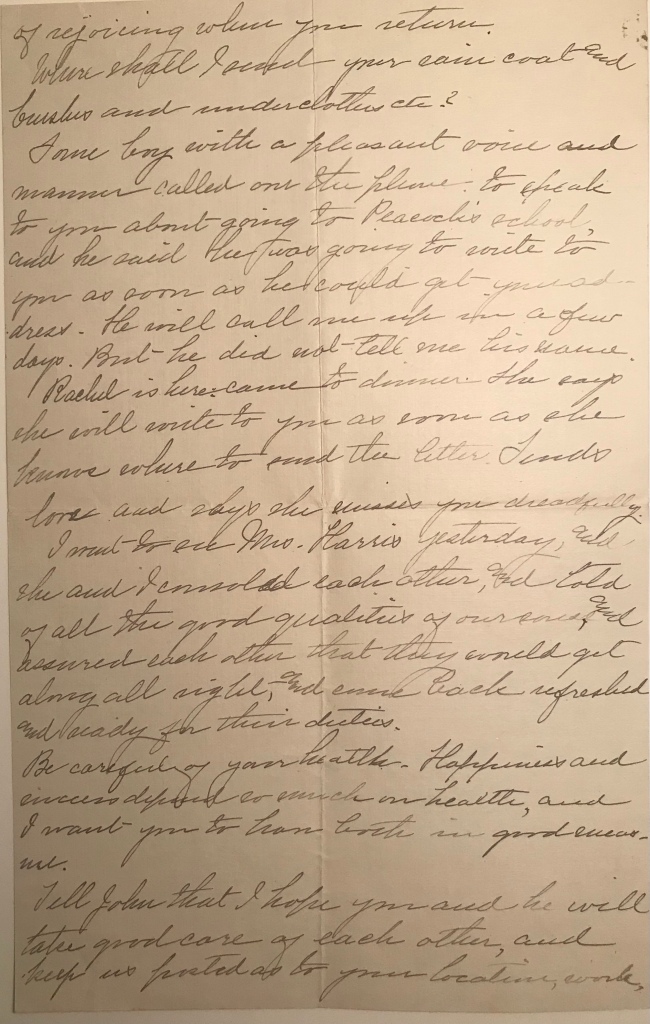

I want you to come home and enter Peacock School or some other good school so that you may prepare for [?] next Fall or the year following. A year lost for school now will hurt more than a year of life lost when you are older. Don’t go on in this way; Don’t waste your life. Don’t distress and humiliate your parents. If you will come back to enter Peacock or some other school here write, or wire me, where to send you the money to come on & I will wire it or send it by registered mail.

Yr loving father,

M.W. Beck

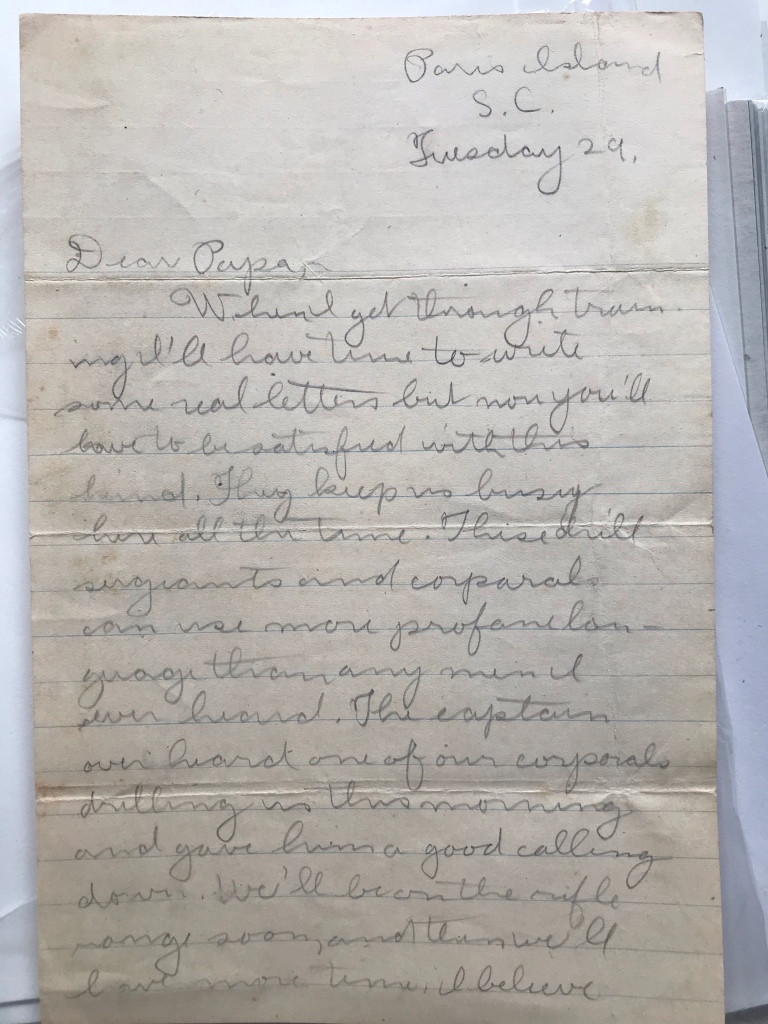

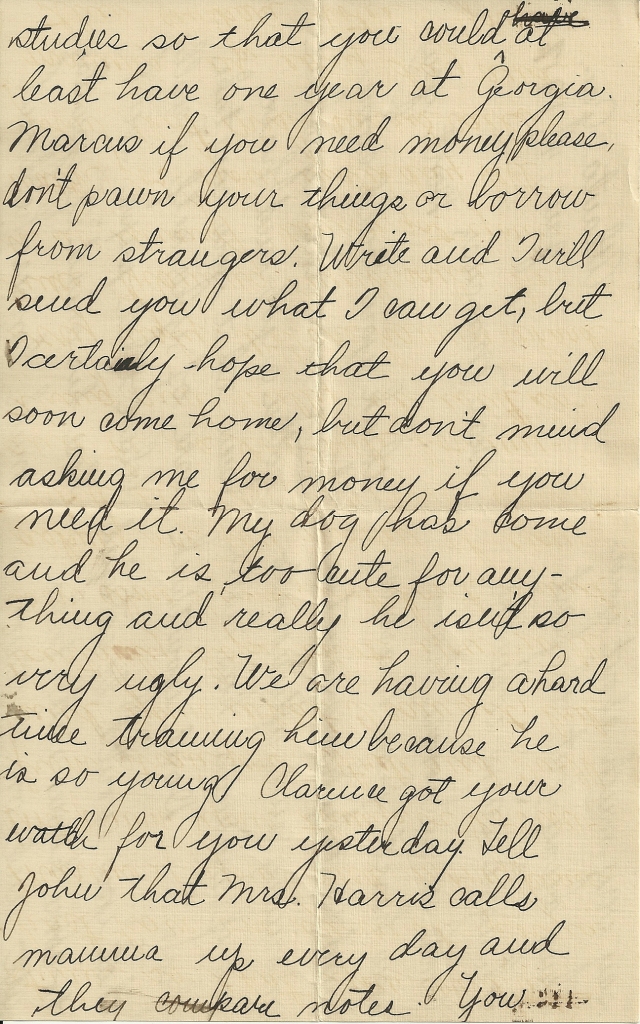

Dear Papa,

You are –

about my at –

leaving [?] –

thoroughly –

myself and –

go somewhere else and show that I could stick with something any way. Do not think that I am not going to college next year for I am. I am going either to Auburn or Fisk and take a special course in architecture. I have not enough units in mathematics so if we do not get jobs in a month or so, enabling us to go to night school and make up geometry we will come back to Atlanta. You said that I only had to stay two years at college and I think it would be better to take a special two year course than break off in the middle of 4 years. Marcus

I think he died though. He died in the war.

A year and a half after he set out

– as so many young people do – as I myself did,

to find freedom,

he died.

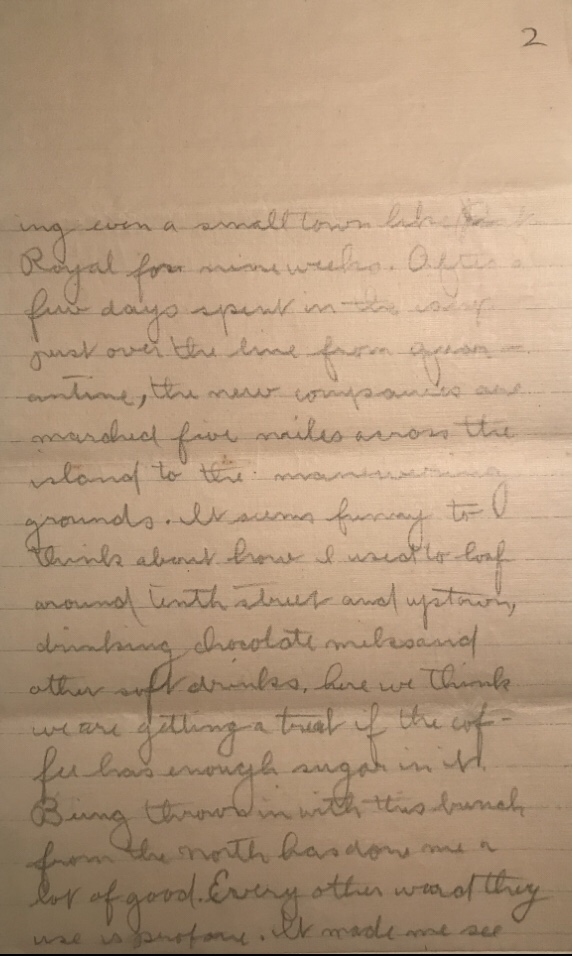

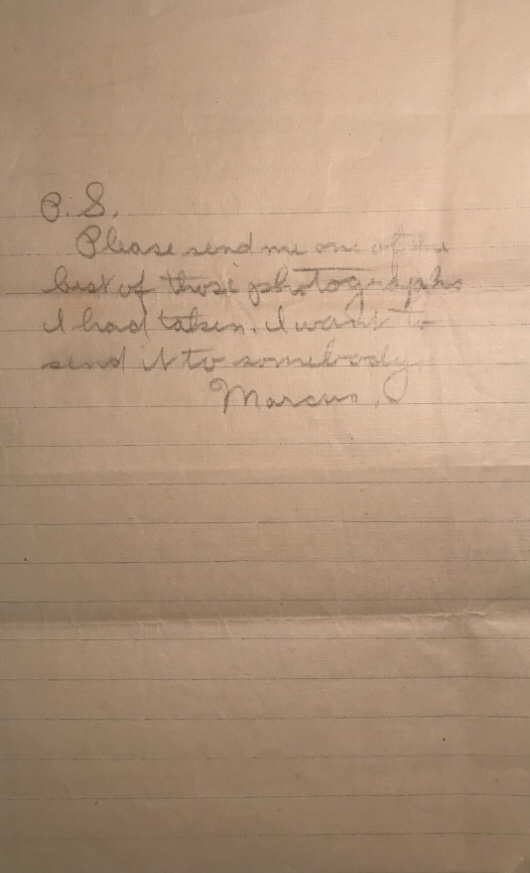

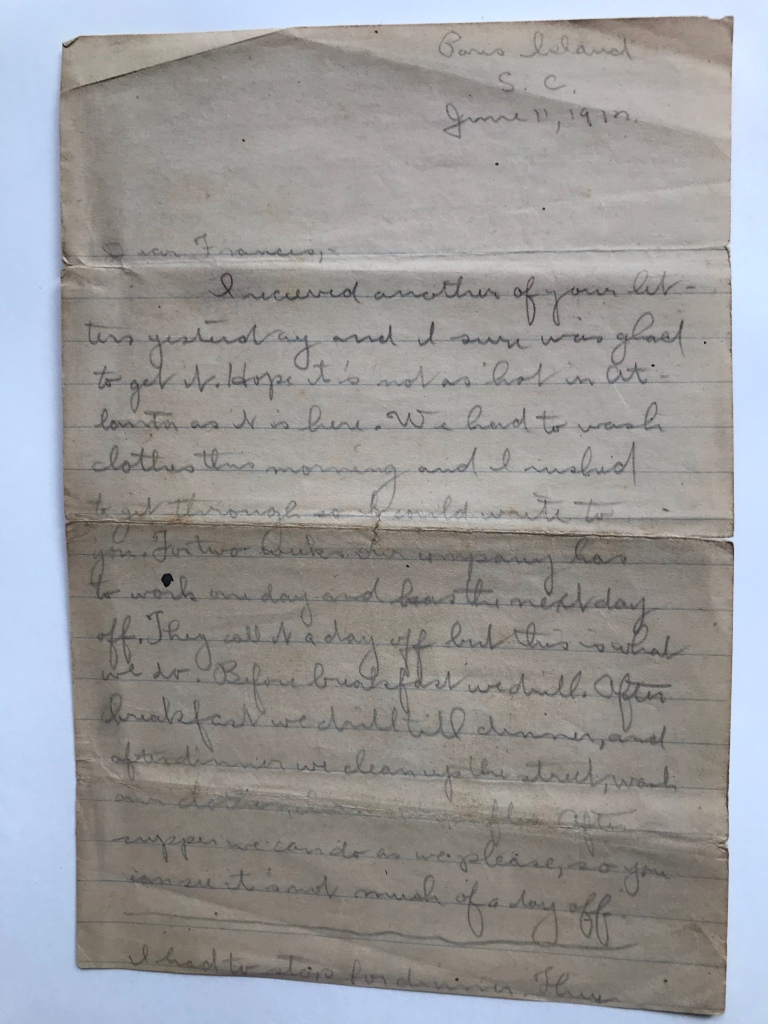

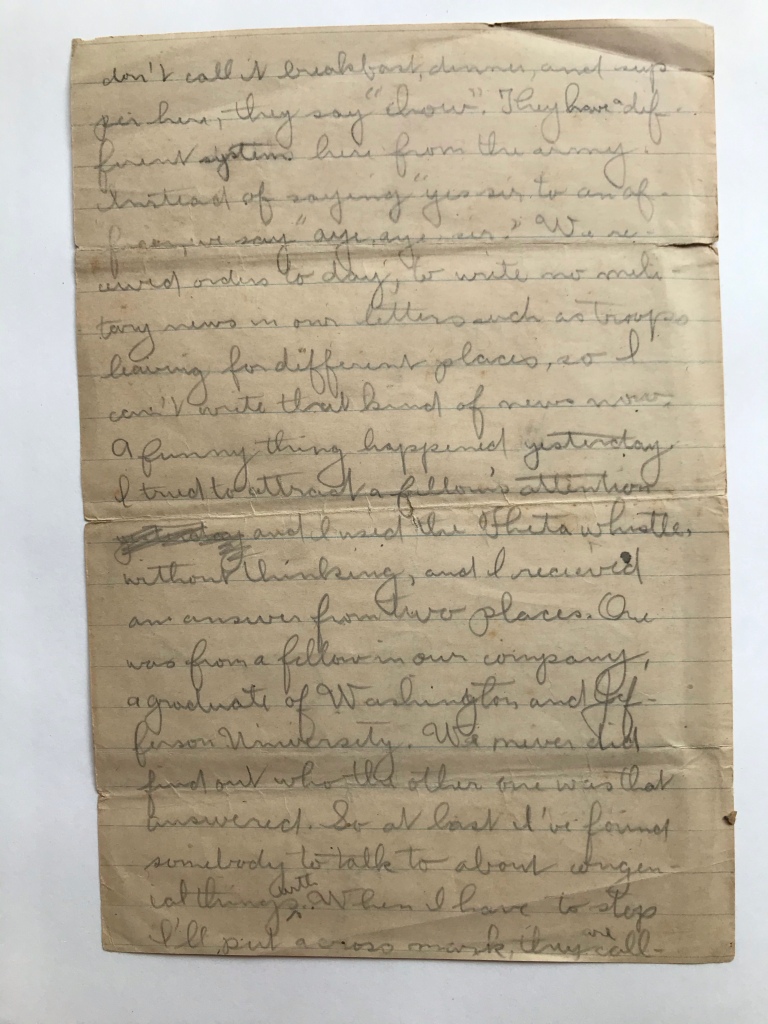

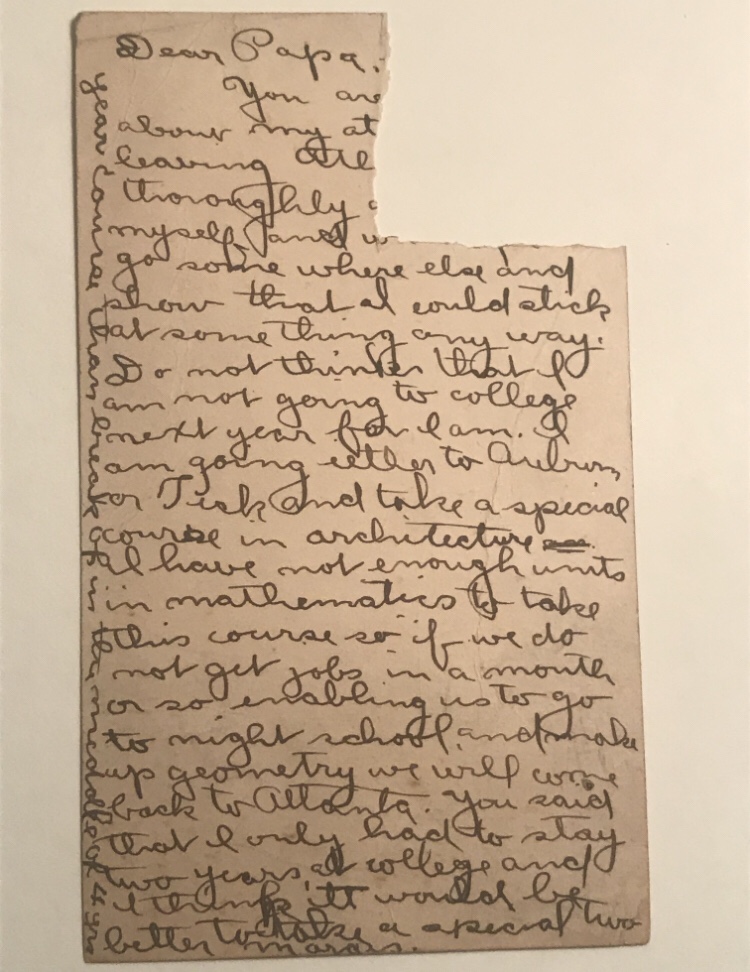

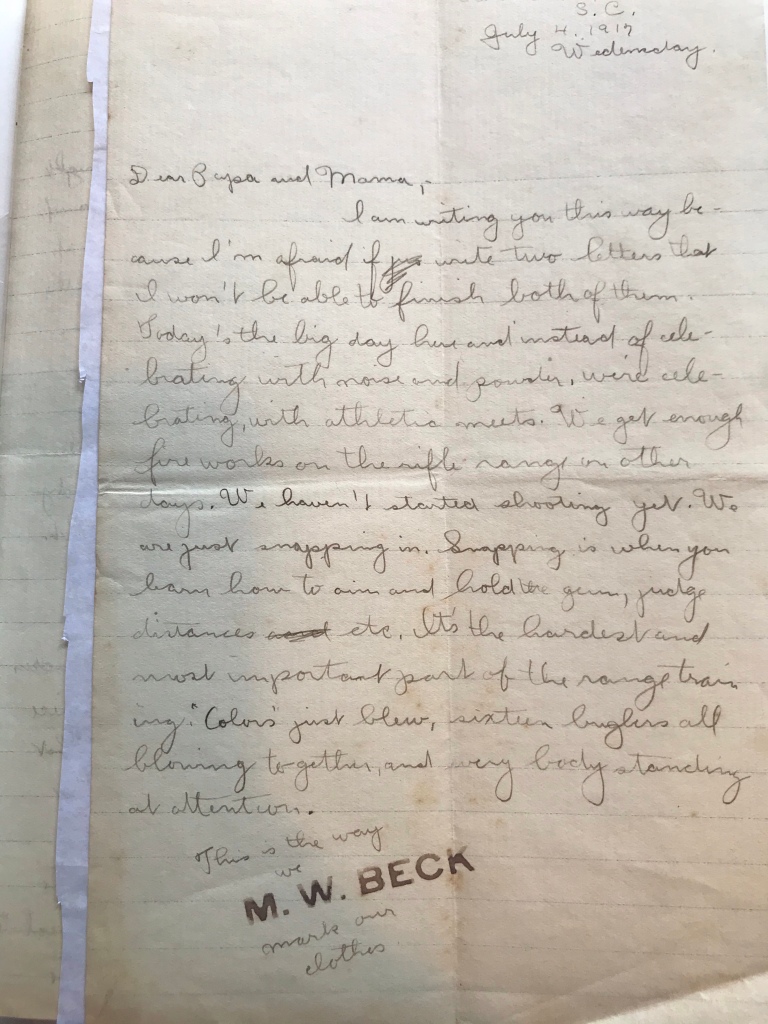

Parris Island, S.C.

July 4, 1917

Wednesday

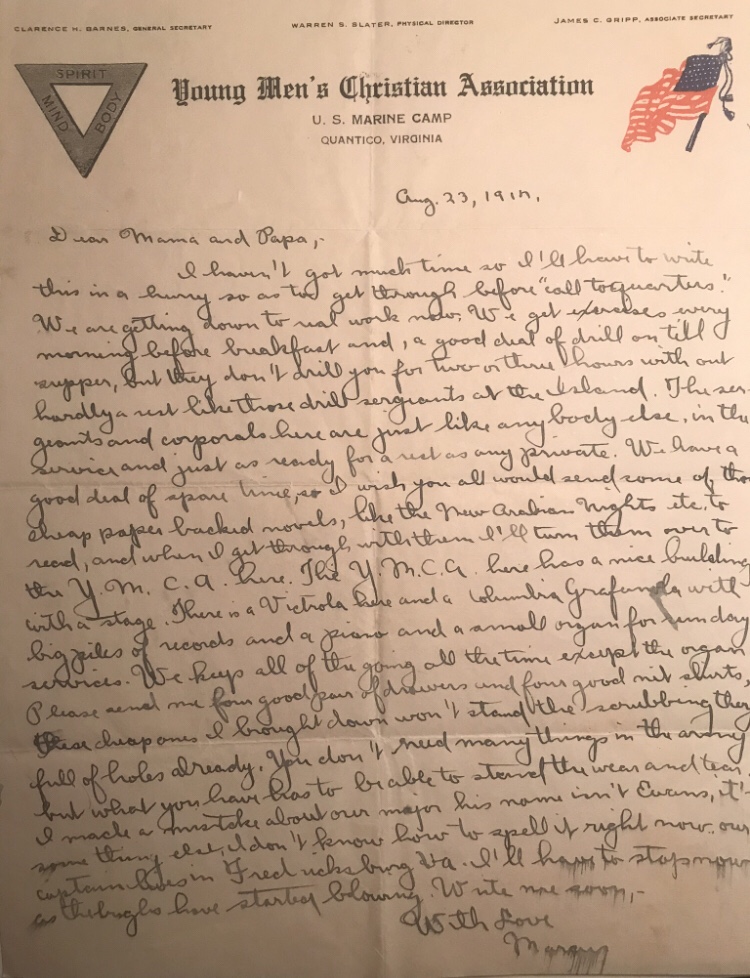

Dear Mama and Papa,

I am writing you this way because I am afraid if I write two letters that I won’t be able to finish both of them. Today’s the big day here and instead of celebrating with noise and powder, we’re celebrating with athletic meets. We get enough fireworks on the rifle range on other days. We haven’t started shooting yet. We are just snapping in. Snapping in is when you learn how to aim and hold the gun, judge distances, etc. it’s the hardest and most important part of the range training. “Colors” just blew, sixteen bugles all blowing together and everybody standing at attention.

[stamp reading M.W. Beck, w/ text reading “This is the way we mark our clothes”]

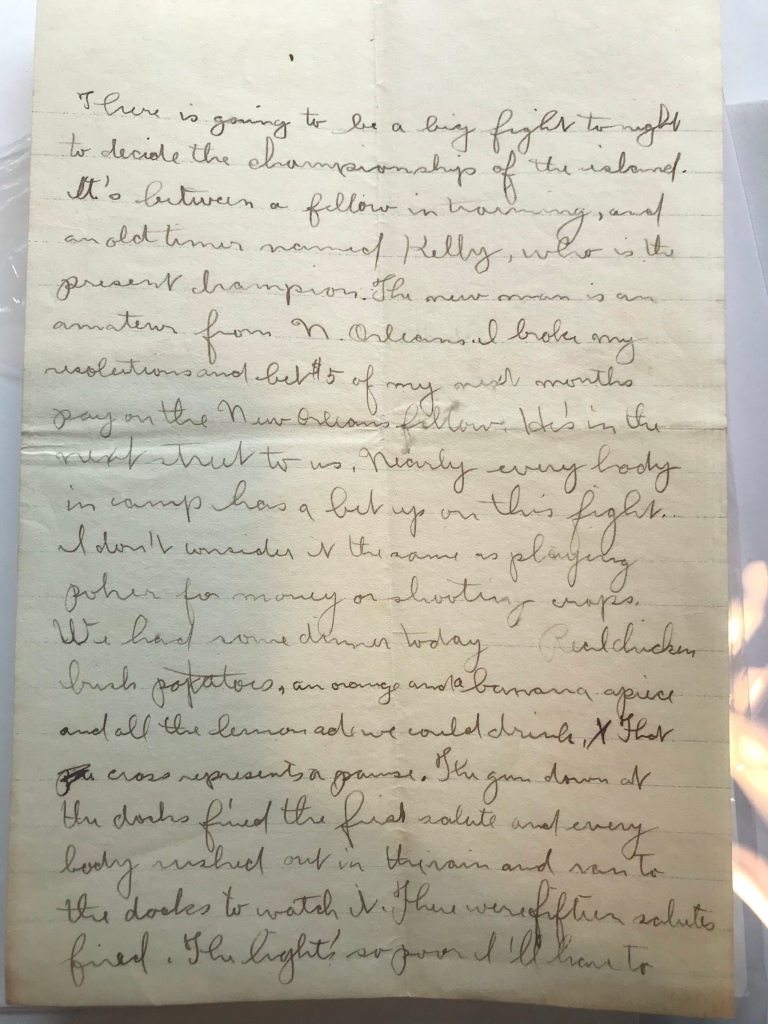

There is going to be a big fight tonight to decide championships of the island. It’s between a fellow in training and an old timer named Kelly, who is the present champion. The new man is an amateur from N. Orleans. I broke my resolutions and bet $5 of my next months pay into the New Orleans fellow. He’s in the next street to us. Nearly everybody in camp has bet up on this fight. I don’t consider it the same as playing poker for money or shooting craps. We had some dinner today. Real chicken, (unreadable) potatoes, an orange and a banana apiece and all the lemonade we could drink. X That cross represents a pause. The (unreadable) down at the docks fired the first salute and everybody ran out in the rain to watch it. There were fifteen salutes fired. The light’s so poor I have to

[end of page]

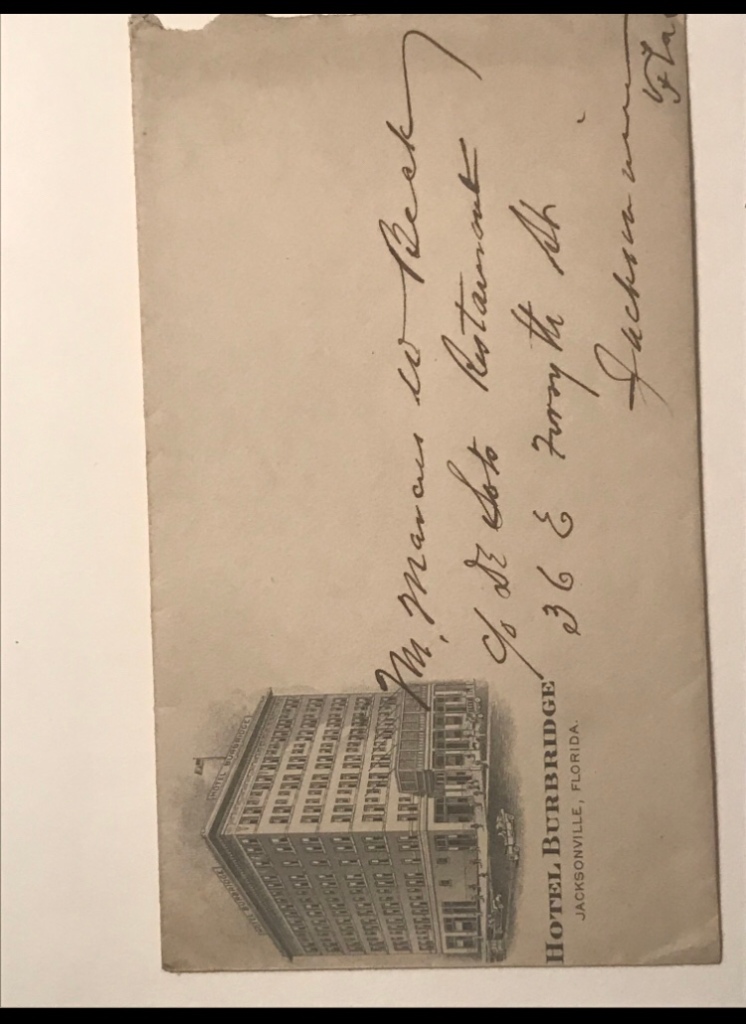

I just got home from Fairview, where my father – as he folds old shirts he calls Hawaiian, but that are really more Floridian, with dolphins and colonial compasses and sportfishing boats – tells me again that I should just get in touch with the people at the University of Georgia and tell them that we have all these old family papers, original documents from the life and career of Marcus W. Beck, whose journals are archived at the university and who is of historical significance due to him being a Georgia State Supreme Court Judge during the first quarter of the 20th century, as WWI unfolded, raged, and took the life of his namesake son following a year of tense rebellion that produced a thick sheath of correspondence between young runaway Marcus, his father and mother, and his sister Rachel, who was my great-grandmother and who I was raised with until her death when I was 16, in 1992. Rachel kept the letters and papers in a closet upstairs in an unused room on the northwest side of the house, perched above the bright blue hydrangea that bloomed and nodded heavily in the shade alongside a dirt road that I still dream about frequently.

Rachel Beck was born in 1894, and so I grew up in the 1980s in South Georgia just down the road from a person I loved that was born in another century.

Marcus W. Beck was significant not for groundbreaking legal decisions that changed legislature, or for his authorship of seminal works of law, ethics, or literature, which – to my knowledge – he was involved in neither, but because in April of 1928 – on behalf of the South – he accepted the as-yet-unfinished monument to Robert E. Lee at Stone Mountain, Georgia, a monument that over the next 40 years would become the largest confederate monument in the United States.

Judge Beck accepted the monument on behalf of the South via a speech that my father tells me that ‘some article somewhere’ reported was a lengthy speech on an unseasonably cold and wet day in early April, 1928.

[Insert excerpts of speech content] [Note: January 4th, 2022 ~ It has been several months since I actively worked on this project, though it has been with me every single day as the pressing haunt of a family curse that my belief in may be considered by some clinical sorts operating from a 21st Century whiteheteronormativeempiricistwestern worldview, where there is no such thing as ghosts and the dead don’t trouble the living. That’s not the world I live in, nor is it the world I was raised in. It is not appropriate or just to impose the assumptions and parameters of one’s world onto the worlds of others. It is a violation. If other people want to live in a genuinely dead world where nothing means or does anything other than the most suggestion, the most clear purpose in a mechanistic and commodified consumer culture, that’s fine. I prefer to live in a world where everything – even the dead – is alive, and has been alive for as long as the Earth has existed. That is the world that makes sense to me, being the person I am and being from where I am from. My beliefs – which is formulated through direct experience put through variable rigors of logical consideration of various possible interpretations – as they pertain to matters of ghosts, family curses, etc. are not that strange at all. I am the daughter of a haunted family, a family haunted by its own history and multigenerational moth-balled stifling of any sort of actual remunerations, reparations, healing or reconciliation at all. Just as my great-great Uncle Marcus saw, our lineage – our blood, the knowings carried in the nuances of fear and shame we pass down – is not just tied to injustice, but shackled also to a shocked sort of grief. I have no idea why Judge Marcus W. Beck read the Bible 30 times, but it seems to me that only a very righteous or a very doomed soul may be so motivated. I have in my possession Judge Beck’s copies of Dante’s Inferno and Paradise Lost. There are notes made in the margins, cantos noted with an asterisk, a line along the edge of the page. I have not studied those notes, nor have I read – in it’s entirety – the speech that Judge Beck gave on April 9, 1928. It’s a very long speech, and although I have only skimmed through the booklet the speech was printed in – a transcription of the entire ceremony that cold, rainy day at Stone Mountain – it seems that in the pages and pages of my great-great grandfather’s speech – he isn’t making much sense at points. There are bizarre references to literature, peculiar divine references. I have wondered if he was drunk, or 1/2 mad, he must have been a man possessed – to go on so long as he did as people waited in the rain for the ceremony to end?

On April 9, 2028 – if I am living – I am going to do an Un-Performance in which I read the speech backwards and allow myself to enter into whatever diction, cadence, stumbling, retching, holler or silence I may feel or happen into as I gesture toward un-doing at least one of the mistakes Judge Marcus W Beck made. I have already begun to facilitate my emergence as a new media artist, a narrative artist, an interesting voice, an interesting story.

Six years should be enough time to make arrangements for a suitable Un-Performance, all proceeds from which will – of course – go toward efforts to have the monument sandblasted or otherwise removed with minimal additional damage to the stone face of the mountain, to Black communities in the Stone Mountain area, and to identified tribal nations who may be down lineage from the people who held that truly ancient monolith to be sacred.

In his acceptance of the monument, Judge Beck offers a thorough example of the idolatry of Robert E. Lee and other Confederate leaders that is part and parcel of the revisionist history of the Civil War known as The Lost Cause. The Lost Cause narrative is the substance of an imagined Confederate heritage, a story that one can and should be proud of.

Millions of people in the American South have been told that this is their heritage, a heritage to be proud of and to defend, a noble resistance to threats to the ‘way of life’ in the South led by brave and capable men.

The Myth of the Lost Cause is…a myth…epic story spun to tell people what is real and what is true, a story to teach a lesson, to shape our worldviews and our identities.

The Myth of the Lost Cause was designed to not only justify, but glorify an act of treason orchestrated to protect the interests of those who profit from slave economies and to preserve a ‘way of life’ that was perceived as being under attack by the efforts to abolish slavery.

This alternative version of history promotes a deeply biased, factually inaccurate, and aggrandized story which uplifts and benefits the character of the (white) Confederate Southerner and proffers a sense of distinct historical and ethnic identity that exists in what seems to be a confused, tense, but generally compatible relation with the similarly white supremacist United States of America, a country whose dominant culture all but demands assimilation into a peculiar brand of English-speaking consumer capitalist culture in which only smatterings of the diverse languages and life-ways of ancestors from all over the world survive only in the form of phrases and food, clothing styles and sacred symbols that have long since been appropriated by the trend fashion industry.

My father is unfolding the shirts and now putting them on hangers, telling me what I should say to the university librarian when I offer to give them our family papers for the purpose of making them available to study. “Just tell them these papers were discovered, primary source documents, and that we want them to be placed in archival…”

“I know what to tell them, how to get in touch with people and what to say.”

Did my father not realize that I had secured over ½ a million dollars in grants for nonprofits over the past year, while doing other work no less, and that I have a Master’s degree?

My ego felt stupidly wounded and I watched a blithe blankness spread over my father’s face as I went on speaking. It is hard to listen to me sometimes.

“I am not going to have them donated or archived until I have a chance to look at the documents and work on them. I mean, this is why I studied sociology, this is why I have a degree in Black Studies, and learned how to do content analysis on media messaging about race, and why I went to the University of Georgia to study under Dr. Beck who researched lynchings and lynching culture and even though that didn’t work out, I still think that it is not entirely out of my wheelhouse to put together an essay or an account of the family papers, particularly as they relate to Judge Beck and Marcus and the monument at Stone Mountain. There are two pieces of legislation right now in Georgia that are focused on the future of Stone Mountain and some groups are actively advocating for the removal of the monument. It is a big deal. The largest Confederate monument in America. I want to at least put together and publish one or two essays and an autoethnographic piece about the papers and my ancestry, so that if someone does decide to work with the papers, I can possibly work with them and learn more about how to do archival documentation and analysis.”

I want to explore how my knowledge of my ancestry, knowledge that for many years was slightly outside of my conscious knowing, but that still was evident to me in the dissonance that I lived with knowing that my great-great grandmother, Judge Beck’s daughter, was a white supremacist.

My father explained her racism as a matter of being a ‘product of her times.’ This concept – that people can become who they are based on when and where they grew up – seeded a sociological curiosity that exists to this day.

I hardly know anything about her, but recently found a 47 page handwritten letter that may be from her to her brother Marcus.

It is also important for me to reflect on the ways that not knowing my family’s history has also shaped me.

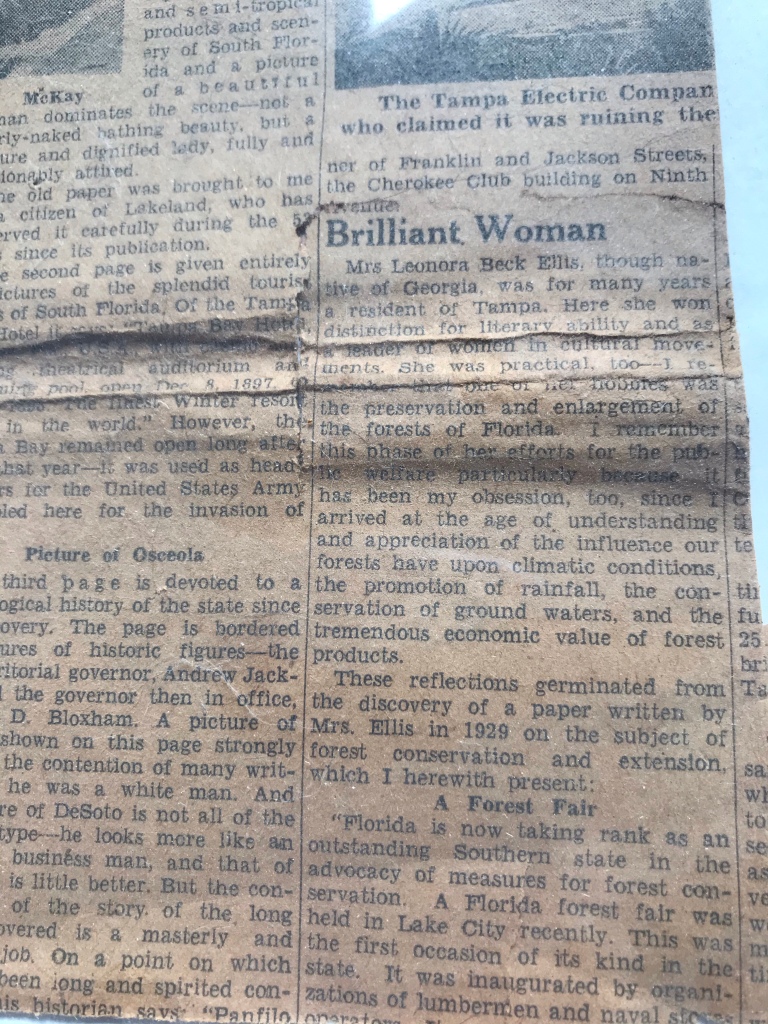

The knowledge that Leonora (“A Brilliant Woman”) had existed, along with more information about Marcus, Jr.’s love of and skill in drawing and his still-developing and yet radical perspectives on justice and politics, may have situated some of my least validated and most authentic character attributes in relation to my ancestry and – perhaps – offered me the opportunity to imagine the encouragement of my long-dead relatives as I floundered in becoming an artist, an activist, a social scientist. (See above caption)

The video above is not fantastic. It may not load on some devices. That’s okay.

Note unplanned awkward efforts to be sensitive to the fragile egos of reactionary good ‘ol boys through learned non-confrontational messaging and mealy-mouthed phrasing.

This reflexive social behavior has its origins in gender socialization to be pleasant and non-angry, as well as extensive social learning re: how truly difficult it is to interact with indignant, offended redneck dudes, with the sub-legit fear of pissing off the wrong Confederate fanboy, because some of those folks are delusional and armed.

Cringe-worthy in moments, this currently unlisted video features me speaking about how I want to see the Confederate monument at Stone Mountain removed.

Additional information about the history and possible futures of Stone Mountain are included in the video’s description on YouTube

I just got home from spending several hours – four, actually – on sorting out the family papers. My intent was to simply revisit the speech at Stone Mountain, for the purpose of doing a more thorough content analysis, but in the process of finding the speech pamphlet again, I had to go through a lot of boxes of old papers – lengthy letters, photos, and documents, invitations to weddings, sympathy cards and newspaper clippings.

“I’ll get the box out for you,” my dad said, and proceeded to pull all the boxes out of the deep closet set into the slope of the roof in the loft room where my family now stores our papers, at least some of them. Old tax records are kept in a different closet across from the bathroom downstairs, with the toilet paper and my mother’s robes, a laundry basket filled with miscellaneous personal care products that my mom found on sale or was simply stocking up on.

Before going upstairs, I asked my mother to begin writing down what she knows about her father’s family, Lebanese immigrants in the 1890s. She began to tell me right then and there the names and places and the story of how my great-grandparents arrived in America and went to Albany as they had planned, but ended up in Georgia, not New York, and were resigned to stay due to having exhausted their money for traveling and – besides – they were already there.

As I was talking with my mother about these things and getting ready to go upstairs and look for the speech again, to capture what was on the pages I’d missed in my first quick documentation of my great-great grandfather’s acceptance (on behalf of the South) of the unfinished bust and head of Robert E Lee that was carved into Stone Mountain, Georgia.

I don’t know why it is that I believe my ancestor’s acceptance of this monument – on behalf of an entire region, no less – somehow ties me to the responsibility to have it removed, to right wrongs done through – at the very least – the erasure of false idols from recent history, the symbols of men that have become enmeshed with a particular brand of Southern white supremacy, in which the old ways of being and the heritage of many white-identified Southern families are entangled with the brutal enslavement of millions of people who were kidnapped from their African home countries in a model of exploitative colonial capitalism that exterminated millions of indigenous people and stripped away the actual heritages of the diverse ‘European’ people who were designated ‘white’ in the ham-handed delineations contructed based on observable physical phenotypes at the expense of everything we really are and who our people really were. Not false wartime idols, but our real ancestors, our real heritage.

My father – again – was going on about talking to the archival people at various universities and I had to tell him again and again that it is important to me to be able to have the opportunity to look at the papers and do some work with them, to take an inventory.

“Yes, an inventory is a good idea, so that when we talk to the archival people, we can tell them what we are donating.”

When I talk to him about autoethnography and the current cultural relevance of white Americans unlearning the bad ideas that are woven into our National and regional identities, and – furthermore – it’s Stone Mountain! The biggest most atrociously tacky Confederate blemish in the country, accepted on behalf of the South by my great-great grandfather…my father seems to think I am foolish and that I don’t know what I’m talking about no matter how clearly, concisely, and intelligently I speak. I explain that if we just hand the boxes over to the University of Georgia, and don’t have our own digital archives, we will be relying on a university library to make the materials accessible beyond traveling to a climate controlled basement 4 hours from here to study the papers for a limited amount of time.

People who may want to learn about their distant relatives will not be able to ever see them, and it’s a good story, not just for scholars.

“Well, that all sounds good.” His tone is ambivalent, if not slightly doubting. “Then we can get things to a point where the scholars can have access to them.” He paused and glanced at me, “…and the wanna-be scholars.”